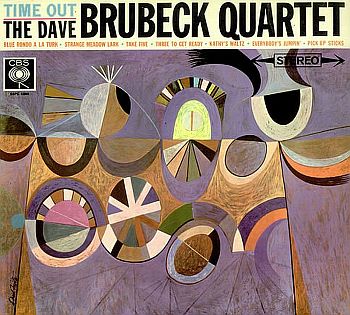

The origins of Time Out & Take Five - Dave Brubeck

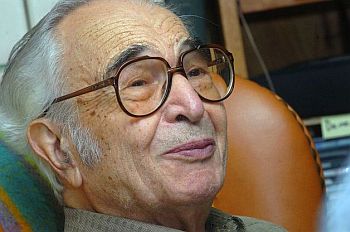

Dave gave thousands of interviews over his long career and invariably since 1959 he was  asked about one the biggest selling jazz albums of all time, Time Out and also the first jazz single to sell a million copies, Take Five. The most definitive version Dave gave was in an interview to Columbia Records at his home in Wilton on September 12, 2003. This interview was subsequently included in the Columbia Legacy 50th Anniversary edition of Time out released in 2009. (Copyright – Columbia Records )

asked about one the biggest selling jazz albums of all time, Time Out and also the first jazz single to sell a million copies, Take Five. The most definitive version Dave gave was in an interview to Columbia Records at his home in Wilton on September 12, 2003. This interview was subsequently included in the Columbia Legacy 50th Anniversary edition of Time out released in 2009. (Copyright – Columbia Records )

Well, I wanted to do an experimental album using time signatures that weren’t usual in Jazz.

If you’re alone and just riding miles and miles with just nothing but you and your horse and the horse going along at a steady gait, I would start thinking of rhythms that I could hear from the horse’s hooves. I could hear how to put a different beat against that. One, two, three, four, five. And get maybe 5 against 3, against 2. That was kind of the start of the way I thought about rhythm.

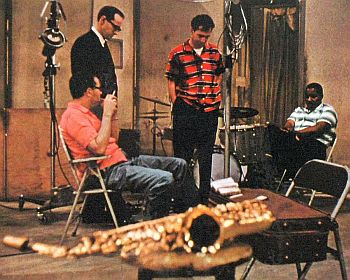

When I brought up the idea with my quartet of doing this experimental album, Joe Morello was so pleased that he would be able to do more compound times playing in different time signatures. Paul was always sceptical of any new move; he didn’t get excited about doing things in different time signatures. Eugene Wright would think “How I am going to hold this together”.

As a leader you gotta be part psychiatrist and get your ideas over in a rather delicate way. We had a successful recording. We were doing odd things.

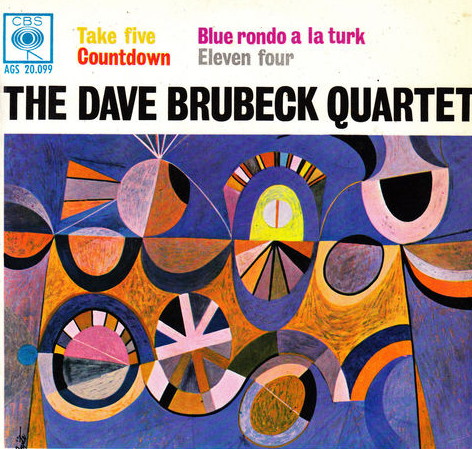

Blue Rondo A La Turk was a street rhythm that I heard street musicians playing in Istanbul.  The rhythm fascinated me so much there was one Turkish musician, I remember his name. His name was June 8th; he was born on June 8th so that was his name. I asked June 8th “What was this rhythm, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3”.

The rhythm fascinated me so much there was one Turkish musician, I remember his name. His name was June 8th; he was born on June 8th so that was his name. I asked June 8th “What was this rhythm, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3”.

June 8th said “That to us is like the blues to you. We all grew up improvising in that rhythm”. So I said, I’m going to use this rhythm in a tune and I will call it "Blue Rondo A La Turk". I should have just called it "Blue Rondo" because the title confused people.

As musicians we are so aware of what other people aren’t aware of. Other people can be scientists; I’m missing everything that they are aware of. But that’s the way life is. Some of us are musicians; some of us are something else. But you are very aware of sound, of rhythms, of just the wonderful noises of the world.

Wherever I go, sometimes its crickets, the sound of the water in the stream outside.

Strange Meadow Lark was really my imitation of the Meadow Lark I remember in Northern California.

Sometimes it’s the wind. I remember one night it was blowing a diminished fifth all night long and it was really loud. And I said, “Someday I am going to use that in a piece”. I’m always paying attention like so many musicians to the sounds around them, that other people don’t hear. There was a gasoline engine and it had craziest rhythms I had ever heard. They weren’t steady like the horses beat. And I would try to put a steady rhythm against this exotic crazy rhythm of the gasoline pump.

Everybody’s Jumpin has a drum solo where Joe Morello plays the melody of the tune on his various drums. And you can really hear it. Not just the rhythm but I can almost hear the melody itself. I don’t know whether I’m putting it in my mind or whether you can hear it in the drums or the cymbals. Joe was such a different type of drummer in those days. And he could play so many complicated things. I remember when we went to India that the Indian musicians really thought that Joe Morello was the first great western drummer that that they had ever heard.

Three Get Ready & Four To Go. A play on words because the first two bars are in three. One, two, three. One, two, three. And then it goes into four. Four to go. So it’s One, two, three. One, two, three. One, two, three, four. One, two, three, four. One, two, three. One, two, three.

I was once eating in a restaurant where there was a radio in the kitchen, a typical jukebox and then some kind of piped in music into the restaurant proper. All three of those I could hear at the same time. I know that no one else was even bothered and it would be stupid of me to complain to the manager that this was probably driving his waiters and waitresses crazy but they don’t why. It was driving me out of my mind!

Kathy’s Waltz was named after my daughter Catherine who was always dancing and dancing really funny steps. So It starts as Kathy jumping around the room in 4/4 and then goes into a waltz which is Kathy’s Waltz.

We depended on each other so much and listened to other so much. Paul would often say things through his horn to me by playing the melody of another tune. For instance he’d say to me – “Dave, quit playing in three keys at once”. This would be after a set. Maybe on the next tune I’d forget and be playing some wild harmonic things. In the middle of his solo he’d play “You, you’re driving me crazy. What did I do to you," Or he’d play “Give me land, lots of land in the starry sky above. Don’t fence me in.”

That if’s he played a chord that he didn’t like that would prevent him from going where he wanted to go. He was fenced in. Joe would do it on the drums back to him sometimes. So you’d have a war of tunes going in the quartet! It was a lot of fun.

Pick Up Sticks, meaning drumsticks. I don’t know why I called it that. It might have been an inside joke because Paul did not want Joe to play with sticks because he wanted Joe to play softly with brushes. And that argument was going on at that time when I wrote "Pick Up Sticks"!

We depended on Eugene to be the rock bottom what the bass man should be. He had to be like a giant back there, holding this group together.

Take Five

I said “Call It Take Five” and Paul said, “Take Five? Why did you wanna call it that?” I said, “Well, it’s in 5/4 time. It’s a thing that people say a lot”. He said “I never heard anybody say ,Take Five”. I said “Paul, you’re the only guy in the world that never heard anybody say ‘Take Five’.”

I said “Call It Take Five” and Paul said, “Take Five? Why did you wanna call it that?” I said, “Well, it’s in 5/4 time. It’s a thing that people say a lot”. He said “I never heard anybody say ,Take Five”. I said “Paul, you’re the only guy in the world that never heard anybody say ‘Take Five’.”

Oom, junka, junk, boom, boom. Oom, junka, junk…That’s the way Take Five opens and I don’t stop that beat from the time of the introduction to the end. In many ways, it’s the tune I look forward to probably the most of the evening. It’s “How far out are we going to go on one chord progression?”

And sometimes the dancers would get into a beat that was just like the groove that the band was setting up. And the whole hall would start rocking!

Because I’d heard Joe Morello playing this 5/4 beat and Paul playing against it. And this would be backstage at a concert when you’re warming up. So I said to Paul, “Now, you, for the next rehearsal, write something in five”. I’ll never forget Paul coming into my house and he said “I can’t write anything in five”. I said, “Well Paul, I heard you play against Joe in five”.

All I wanted was, like, a beginning for a tune and then a drum solo for Joe to play a drum solo in five. Paul said “I can’t do it”. And I said “Well, what you wrote down any of your ideas?” He said “Well I wrote down two themes”. I said “Well, let me hear them”. He played one theme. Then he played the other. In fact, on this piano right behind me, that piano in Oakland, California is the first piano that ever heard those two themes.

And I said, “Paul, we put those two themes together and we’ve got a typical jazz tune, except it’s in 5/4 time”. Even Paul liked it. Joe liked it. So we rehearsed it right in my front room. So that’s the way the tune was born.

Time Out

I thought “I’ll just go to Columbia with this new album and I won’t say a word about it because I know they won’t like it”.

I thought “I’ll just go to Columbia with this new album and I won’t say a word about it because I know they won’t like it”.

Why?

- You’ve got all originals on this same album.

- You can’t dance to it.

- You want a painting on the cover.

- We’ve never done that before. We just can’t present this album as you like it and as you’ve written it.

There was only one person that liked it and that was the president of the company. His name was Goddard Lieberson. He was president of Columbia and he was a composer, and arranger and somebody that everybody that I knew respected him. He said “Dave I’m so tired of hearing Stardust and Body and Soul. This is so fresh”. He said “Give me a copy of Blue Rondo a La Turk and Take Five. I’m going to the West Coast to see all the Columbia representatives out there tomorrow and I wanna bring this new idea of yours and play it for them.”

When he came back I asked him “How did it go?” and he said “Nobody liked it”. It didn’t make a big noise at the beginning at all. No one was advertising or behind it.

But the disc jockeys, one in Cleveland and one in Chicago started playing this. And pretty quick, they had an audience requesting it. Requesting it so much that the Columbia sales people finally realise “This thing is becoming popular”. It took a long time before Take Five and Blue Rondo came out as a single.

We went on tour to Europe with the quartet. We heard rumours that we had a hit record going on back in the States. And when we came home from Europe, we discovered it really was a hit and nobody could understand it.

It’s strange how it was across-the-board acceptance of the Time Out album. When we’d pull into a campus in our cars or big band bus as we drove down Sorority or Fraternity Row, you could hear Time Out coming out of each new building. It was such a wonderful experience to have all these doors that had been so closed, be opening. And I loved that whole period in my life.

And when they said people can’t dance to it... some people couldn’t dance to it. They’re not used to dancing in five. Detroit was a great place to play in the dance hall. Boy, they could dance in 5/4 time to Take Five. They could dance anything we’d play.

42 years ago, I didn’t expect any success, except the wonderful feeling of doing something new and creative. And regardless of whether it would be a popular record or not, I just thought I had to break with this 4/4 march-style jazz. These tunes, kind of, opened the door for a lot of really great guys to step through and do something that’s even more complicated, a lot more complicated.

When I started travelling the world again, after Time Out was out, I saw people dancing to this all over the world. It was still on jukeboxes. It was being played on the radio. So that was wonderful, to think that this album that was just an experiment is still so popular all over the world.