.jpg)

Dave Brubeck,The Humanitarian

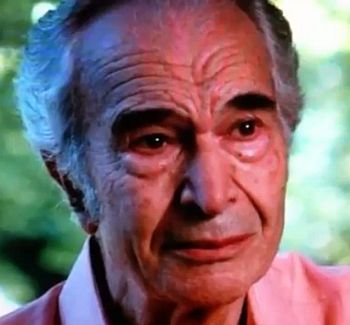

The Fight Against Racism

Chris Brubeck in a very moving piece written about Dave after he died discussed Dave’s humanity and his intolerance of racism. A few years ago, when my Dad was already older, he agreed to sit with Ken Burns and his crew to talk about his memories and the meaning of jazz in America. I wasn’t there (madly writing on deadline across town) but later in the day I called Dad and asked him how the interview went. My father told me that he blew it. I asked him what he meant by that. He said that he talked about racism in America and recalled the story of how his father, Grandpa Pete (the Cowboy), took my Dad as a kid to see a man Pete knew. Pete also knew that this person had been whipped when he had been a slave. Pete told my Dad that that was no way to ever treat fellow human beings. Then this fellow took off his shirt and showed little Dave his scarred back. When my Dad relayed that story on camera, he got deeply emotional and cried. That’s why my Dad said he blew it.

A few years ago, when my Dad was already older, he agreed to sit with Ken Burns and his crew to talk about his memories and the meaning of jazz in America. I wasn’t there (madly writing on deadline across town) but later in the day I called Dad and asked him how the interview went. My father told me that he blew it. I asked him what he meant by that. He said that he talked about racism in America and recalled the story of how his father, Grandpa Pete (the Cowboy), took my Dad as a kid to see a man Pete knew. Pete also knew that this person had been whipped when he had been a slave. Pete told my Dad that that was no way to ever treat fellow human beings. Then this fellow took off his shirt and showed little Dave his scarred back. When my Dad relayed that story on camera, he got deeply emotional and cried. That’s why my Dad said he blew it.

But when the Ken Burns series about jazz came out, Ken himself told me that the story Dave told and his anguish which was caught on camera became the emotional centerpiece of the entire documentary. My father’s humanity came through loud and clear in that segment”.

Dave had told this story previously in interview with Hendrick Smith for the documentary “Rediscovering Dave Brubeck”.

I think I may have been six or seven, but I have to guess. And I don't know what was in my father's mind, but we were together. I used to go with him sometimes when he'd buy cattle. [We were down] on the Sacramento River. And my wife's uncle always hung out with a black rodeo rider. His name, believe it or not, was Shine.

And so my dad just brought me up to this guy and he said "open your shirt for Dave and show him your chest." And he did and there was this brand on his chest. And my dad said "something like this should never happen again.." …You've gotta remember I'm around cattle branding and I know what it's like, that hot iron, 'cause I've branded hundreds of cattle. And the hotter the iron, the less it will hurt and the quicker you can get off, get off the burning and the smell of that burnt hair and skin. So you want to get that fire as hot as you can. And the whole picture came to my mind, because I've been around branding as long as I can remember. And to see a wonderful man having had to go through that was just too much for me….It had an impact on me that I'll never forget. All of my life I thought what I can do about this. It's like my dad telling me to do something about it”.

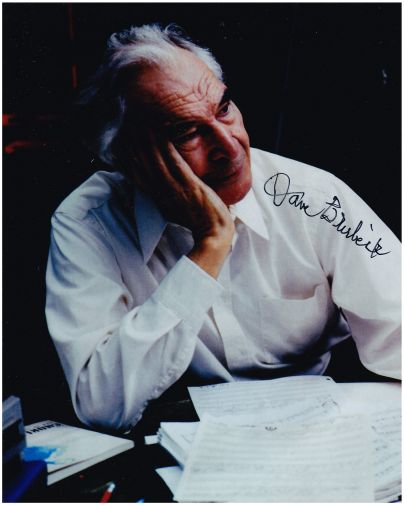

That impact led to Dave Brubeck becoming all his life intolerant of prejudice and racism. He used his music to advocate against such intolerance and to fight for civil

rights and racial unity.

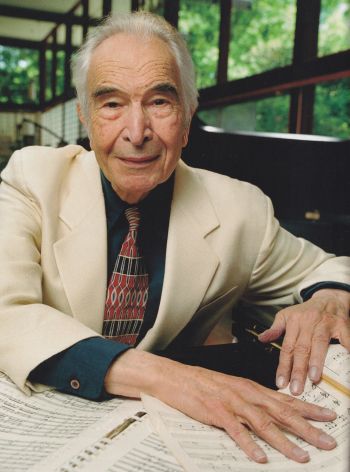

In his discussion with Hendrick Smith, Dave further outlined his fight against racism. “I had the first integrated Army band in World War II. This old Colonel, the one that spoke German, was a humanitarian. And he allowed me to have blacks in my band. It was against principle. I tried to get into a black band. And being white, they wouldn't let me. So I was glad to do it in reverse and bring two blacks into my band. A lot of hostility came from people that didn't think in terms of the equality of man, who were upset by us being what they called 'billeted' living together.”

Dave later in his career had to endure further hostility. In the late '50s, riding the success of "Take Five," the Dave Brubeck Quartet was, alongside the Modern Jazz Quartet, the most famous jazz group in the country. It was also, thanks to the introduction of bassist Eugene Wright, easily the best-known integrated act. Yet despite their fame, the group was turned away from hotels even outside the South, in Minneapolis, Salt Lake City, and elsewhere. But the worst trouble for the integrated band was in the segregated South. Even at university gigs, they required a police escort. A bomb had been thrown at a Louis Armstrong concert in Knoxville in 1957. In 1958, Dave’s manager began to receive letters from Southern universities insisting that the Quartet drop Eugene Wright in order to perform. "We have no integration down here," the president of LSU told the San Francisco Chronicle.

But the worst trouble for the integrated band was in the segregated South. Even at university gigs, they required a police escort. A bomb had been thrown at a Louis Armstrong concert in Knoxville in 1957. In 1958, Dave’s manager began to receive letters from Southern universities insisting that the Quartet drop Eugene Wright in order to perform. "We have no integration down here," the president of LSU told the San Francisco Chronicle.

"It wasn't easy," Dave recalled in 2007, in relation to the sense danger, of being sought out for music but rejected as people. "And we went through many things."

Dave refused to compromise. He cancelled gigs. He took a similar stand on the Bell Telephone Hour, a musical TV program, when the producers made a similar ultimatum. "I told them that we weren't going to change," Dave recalled. "And, they said, 'Well, then we can't have you.' And I said, 'All right, I'm not going to do your television show.' "Jazz stands for freedom," Dave said. For him, it also stood for loyalty and principle.

Dave discussed the matter further when he outlined to Hendrick Smith “All these ridiculous old rules”.

I wasn’t allowed to play in some universities in the United States, and out of twenty-five concerts, twenty-three were cancelled unless I would substitute my black bass player for my old white bass player, which I wouldn’t do. They wouldn’t let us go on with Gene [Wright] and I wouldn’t go on without him. So there was a stalemate and [we were] in a gymnasium, a big basketball arena on a big campus. And the kids were starting to riot upstairs. So the President of the school had things pushing him from every side: The kids stamping on the floor upstairs, me refusing to go on unless I could go on with my black bass player.

So we just stalled and the bus driver came and said, “Dave, hold out. Don’t go on. The president is talking to the governor and I think things are going your way.” And the governor says, “You’d better let them go on.” So we held on and the president of the college came in and he said, “Now you can go on with the understanding that you’ll keep Eugene Wright in the background where he can’t be seen too well.” And I told Eugene, “Your microphone is off and I want you to use my announcement microphone so you gotta come in front of the band to play your solo.” Well the audience went crazy. We integrated the school that night. The kids wanted it; the president wanted it; the teachers wanted it. The president of the college knew he might lose his funding from the state. So here’s the reason you fight is for the truth to come out and people to look at it.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet circa 1960

The Dave Brubeck Quartet circa 1960Paul Desmond, Dave Brubeck, Joe Morello & Eugne Wright

Nobody was against my black bass player. They cheered him like he was the greatest thing that ever happened for the students. Everybody was happy. My point is those students had hired me in twenty-five universities. And twenty-three had to cancel because of what they thought they would lose from the state government. But they wouldn’t lose it. We went back and played all of those schools in a few years. And we’ve had a lot of terrible things happen to us while we’re fighting to have equality - police escorts from the airport to the university, or where I wouldn’t go on [stage] until the blacks could come in or [until they] didn’t have to sit in the balcony. I wouldn’t play until they were in the front row. You gradually stop all these ridiculous old rules that nobody really believes in."

In 1960 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People thanked Dave publicly for his “courageous stand against submitting your band to the pressures of immoral racial discrimination”.

The Real Ambassadors

September 22, 1962, members of "The Real Ambassadors"

September 22, 1962, members of "The Real Ambassadors"taken at rehearsal at St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco a few days

before the performance at Monterey: Back row, L-R: Howard Brubeck,

Danny Barcelona, Eugene Wright, Joe Morello, Billy Cronk,

Dave Lambert, Yolande Bavan, Jon Hendricks, Iola Brubeck

Front row, L-R: Trummy Young, Carmen McRae,

Louis Armstrong and Dave Brubeck.

Brubeck Collection, Wilton Library.

Dave and Iola Brubeck created The Real Ambassadors in the late 1950s. The jazz musical pointed out the absurdity of segregation and made the case that artists such as Louis Armstrong are the best and "real" ambassadors to demonstrate a nation's ideals.

In writing the musical, Dave and Iola drew upon experiences they and their friends and colleagues had while touring various parts of the world on behalf of the U.S. State Department. Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, and Duke Ellington were among several musicians used in a campaign by the State Department to spread American culture and music around the world during the Cold War, especially into countries whose allegiances were not well defined or were perceived as being at risk of aligning with the Soviet Union. Fittingly, The Real Ambassadors was about the important role that musicians play as unofficial ambassadors for their countries. Dave and the Quartet went on a State Department tour in 1958, visiting Poland, Turkey, India, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), West Pakistan (now Pakistan), Afghanistan, Iran, and Iraq.

Among the events referenced, directly or indirectly, in The Real Ambassadors were the 1956 student riots in Greece in which rocks were thrown at the U.S. Embassy which dissipated following performances by Dizzy Gillespie; Louis Armstrong’s 1956 visit to Ghana as the guest of Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah; and Armstrong’s dispute with President Eisenhower and his aministration personally over the handling of the 1957 Central High School crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas.

The musical was performed with Iola Brubeck narrating live at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1962. Performing were the Dave Brubeck Quartet; Louis Armstrong and his band; Lambert, Hendricks & Ross; and Carmen McRae. Television cameras, though present, did not capture the performance, and it has not been performed since.

The Real Ambassadors was able to capture the often complicated and sometimes contradictory politics of the State Department tours during the Cold War era. Addressing African and Asian nation building in addition to the U.S. civil rights struggle, it satirically portrayed the international politics of the tours. The musical also addressed the prevailing racial issues of the day, but did so within the context of witty satire. Below is an excerpt of Louis Armstrong’s opening lines to the piece "They Say I Look Like God".

Dave & Louis performing

Dave & Louis performing The Real Ambassadors, Monterey 1962.

They say I look like God.

Could God be black? My God!

If all are made in the image of thee,

Could thou perchance a zebra be?

He's watchin' all the Earth.

He's watched us from our birth.

And if He cared if you black or white,

He'd a mixed one color, one just right.

Black or white...One just right...

Despite Iola Brubeck's intention for some of her lyrics to be light and humorous in presentation [believing that some of the messages would be better accepted, if presented in a satirical manner], Armstrong saw this performance as an opportunity for him to address many of the racial issues that he had struggled with for his entire career, and he made a request to sing the song straight. In an interview in 2009, Dave remarked on Armstrong's seriousness: "Now, we wanted the audience to chuckle about the ridiculous segregation, but Louis was cryin'... and every time we wanted Louis to loosen up, he'd sing 'I'm really free. Thank God Almighty, I'm really free'.

The Monterey performance was the only one performance of The Real Ambassadors. Dave and Iola hoped to bring it to Broadway but it never reached there. They discussed the matter in an interview with University of The Pacific as part of their archive material.

Iola:

“Well, first, I think there were a lot of different reasons. And, there's one very common, ordinary, everyday reason: cost. I think that Joe Glaser, the manager and agent for Louis Armstrong as well as for Dave, and a lot more money could be brought in by concert tours than the time that it would take to be in a production of a Broadway show. I think that was a very fundamental reason that it didn't happen. And the other reason is that we did hit hard on the racial issue, and that was primarily it, and some other things that were critical of the government that I think maybe producers would be a little hesitant to take on that period. What do you think”?

Dave:

“I think so, and some of your lyrics might have turned them off. Like...."The State Department has discovered jazz. It reaches folks like nothing ever has. When our name is called as vermin, we sent out Woody Herman. That's what we called cultural exchange." And, it goes on and on what she wrote”.

Iola:

“And then, Louis sings “as an ambassador from the State Department that I represent the government, but the government will represent things that I stand for”. I mean, that's pretty blatant. So…..” .

The Continued Fight

Dave continued to use his music to highlight social prejudices. In 1969 he wrote “The Gates of Justice” in the wake of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination. It contemplates the historic struggles of Jews and blacks yet remains optimistic about his overarching theme, the brotherhood of man.

Darius Brubeck, who lived in South Africa from 1983 to 2005, wrote after Dave Died:

“The New Brubeck Quartet (Dave, Chris, Dan and I) toured South Africa in 1976, of all years, albeit before the declaration of the UN cultural boycott. Dave had been an outspoken campaigner for civil rights in the American South in the 1960s and it didn’t take long for him to see that while coming to South Africa may have been a mistake, he could also make demands that might do some good.

He insisted on a local opening act, Malombo and hired Victor Ntoni to play acoustic bass with us. Even though we were self-contained with my brother Chris playing electric bass, this was a way to ‘integrate’ our group. Dave later sponsored Victor at Berklee School of Music in Boston and my parents came to visit us in Durban in 1984. They really loved the country and, as always, made lasting friends.”

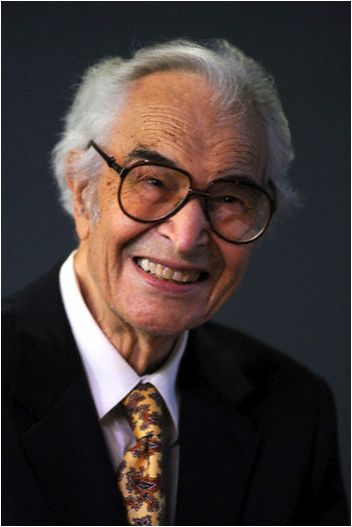

After Dave’s death, CNN wrote a superb article “What The Tributes Missed” (extracts detailed below) behighlighting the role Dave played throughout his career fighting injustices:  Dave Brubeck was inspired by differences. It must be said, that the jazz world Brubeck helped create wasn't a racial utopia. Black artists were exploited. White audiences gravitated to some white jazz artists who didn't have the talent of black artists. Even some white artists like Brubeck were looked at with disdain by some black musicians.

Dave Brubeck was inspired by differences. It must be said, that the jazz world Brubeck helped create wasn't a racial utopia. Black artists were exploited. White audiences gravitated to some white jazz artists who didn't have the talent of black artists. Even some white artists like Brubeck were looked at with disdain by some black musicians.

Ian Carey, a jazz trumpeter who recently wrote the essay, "How Not to Become a Bitter White Jazz Musician," said "white musicians unfairly profited from discrimination against black musicians by audiences and the music industry." Yet Carey also said that when it came time to play, a lot of those divisions evaporated because of something inherent in jazz: "Most jazz musicians don't care how you look. They just care about how you play".

"The bandstand is a great equalizer," he said. "You're going to get the best guy or woman for the gig. It doesn't matter what they look like."

Brubeck applied the same principle to his music. He led the first integrated band in the U.S. Army during World War II. He hired a black man, Eugene Wright, to be his quartet's bassist. The jazz world that Brubeck moved in was full of cross-racial and cross-cultural fertilizations.

They weren't just ahead of their time; in some respects, they were ahead of our time. Brubeck was a champion for democracy as well as jazz. It's often forgotten that many of the exotic rhythms he infused into his music came from tours his quartet took of the Middle and Far East. The State Department sponsored these tours to promote democracy during the Cold War.

Brubeck often compared jazz to democracy, saying both challenged individuals to express their freedom while being disciplined enough to respect the freedom of others. Brubeck’s words about jazz and democracy take on even more meaning with the recent presidential election. Perhaps some Americans feel like traditional jazz purists felt after they first heard Brubeck's exotic rhythms on his groundbreaking 1959 "Time Out" album: My world is changing, and I don't know these tunes.

Brubeck often compared jazz to democracy, saying both challenged individuals to express their freedom while being disciplined enough to respect the freedom of others. Brubeck’s words about jazz and democracy take on even more meaning with the recent presidential election. Perhaps some Americans feel like traditional jazz purists felt after they first heard Brubeck's exotic rhythms on his groundbreaking 1959 "Time Out" album: My world is changing, and I don't know these tunes.

David Simon, the creator of the HBO series "The Wire," captured some of that angst in an essay he wrote right after the election, "Barack Obama and the Death of Normal."

"America will soon belong to the men and women - white and black and Latino and Asian, Christian and Jew and Muslim and atheist, gay and straight - who can walk into a room and accept with real comfort the sensation that they are in a world of certain difference, that there are no real majorities, only pluralities and coalitions. We are all the 'other' now.

Brubeck entered that world over half-a-century ago.He was a white man in a world dominated by black artists, but he wasn't threatened by the differences. He respected tradition but he wasn't afraid to subvert it if it meant growth. He learned how to listen to, and be inspired by the music of 'the other'.

Dave Brubeck was often called the "Ambassador of the Cool," but he was more. He was the ambassador for a new America."

NPR: I Believe

National Public Radio ran a series of essays called "This I Believe". Dave wrote a piece for this series that summarises more than most the idea of “Dave Brubeck, humanitarian”.

National Public Radio ran a series of essays called "This I Believe". Dave wrote a piece for this series that summarises more than most the idea of “Dave Brubeck, humanitarian”.

The Ultimate Victory of Faith, Hope and Love

“I believe in the ultimate victory of faith, hope and love in a world full of conflict and destruction. Faith, that most human of emotions, manifests itself in many different forms throughout the world, and even within the lifetime of one individual. I believe we each are protagonists in a great human drama and it is in our daily choices, large and small, that we contribute on one side or the other in a continual struggle between good and evil, forgiveness and revenge and ruthless power.

In more concrete political terms, I have seen this struggle played out in South Africa, Russia, Eastern Europe and other parts of the world within my own lifetime. I have witnessed the power of an individual faith and a selfless moral compass in a Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Pope John Paul II and others.

At the beginning of glasnost, I was interviewed on Russian television and asked by the skeptical commentator if I really believed it was possible to have peace in the world. I told him that the starting point was for each of us to understand our own religious and cultural traditions, and then open our minds to others, seeking and acknowledging our common roots.

To this end, I recently composed a choral composition based on the Commandments of Moses. The Koran, the Torah, and the Christian Bible recognize these commandments. Others of the world's great religions have a similar code of conduct as an essential part of their belief in a higher law. The great commandment from Christ is to love one another. Similar to Jesus, Buddha taught that the crowning enlightenment is to love your enemies. This thought is expressed in diverse faiths.

A great Native American, Chief Joseph, declared that "the Great Sprit made us all." Science through DNA knows this to be true, the very cells of our body know this to be true, and our great religions know it to be true. Our hope lies in the Great Spirit, the God of all Creation, that my particular faith calls the Holy Spirit”.

Dave Brubeck, aged 7 with brother Howard

Dave Brubeck, aged 7 with brother Howard  Dave playing with the integrated Army Wolf Pack Band

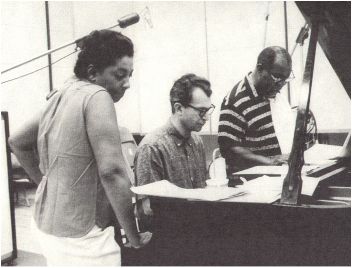

Dave playing with the integrated Army Wolf Pack Band  Carmen McRae, Dave and Louis Armstrong

Carmen McRae, Dave and Louis Armstrong  Iola in rehearsal with Carmen McRae

Iola in rehearsal with Carmen McRae