.jpg)

The Octet, Trio & Quartet

The Fantasy Years - How It All Happened

by Dave Brubeck

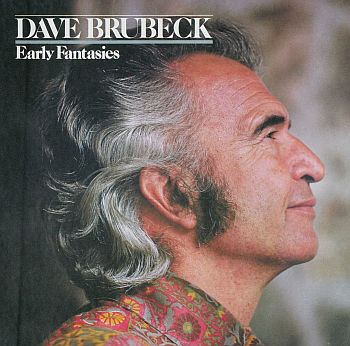

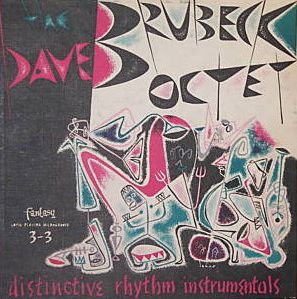

Early Fantasies - The Story of the Octet, Trio & First QuartetThis is the essay written by Dave for "Dave Brubeck - Early Fantasies" - a Book Of The Month Club issue in 1980 consisting of 3 LP's in a box set. Dave documents the origins of the Dave Brubeck Octet, the Dave Brubeck Trio and the first Dave Brubeck Quartet whose recordings were all issued on the Fantasy label.

Early Fantasies - The Story of the Octet, Trio & First QuartetThis is the essay written by Dave for "Dave Brubeck - Early Fantasies" - a Book Of The Month Club issue in 1980 consisting of 3 LP's in a box set. Dave documents the origins of the Dave Brubeck Octet, the Dave Brubeck Trio and the first Dave Brubeck Quartet whose recordings were all issued on the Fantasy label.

Early Fantasies - The Story of the Octet, Trio & First Quartet

Early Fantasies - The Story of the Octet, Trio & First QuartetMost people are familiar with my Quartet recordings, released between 1954 and 1969 when I was under contract to Columbia Records. But there is a loyal group of fans whose memory reaches back even further. Frequently one of them appears backstage with a red vinyl disc and a battered record sleeve for me to sign. These old Fantasy LPs, EPs and 78s, which were issued and catalogued in such a cavalier manner, are referred to in our family as “Pre- Columbian” records.

On re-evaluating my recordings (l’ve made almost 70 albums since those Fantasy years), I feel a great debt of gratitude to the first releases. They established my own career and introduced Cal Tjader, Paul Desmond and other San Francisco musicians to an international audience. The very first sides brought recognition to the Trio.

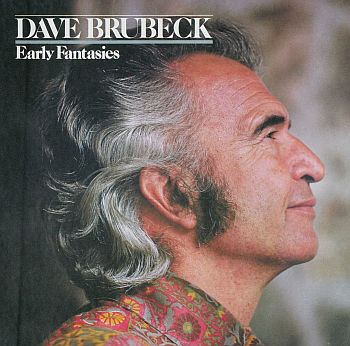

Our first experience in a recording session was at Sound Recorders in San Francisco. The studio was experimenting with the use of tape, then being perfected by the Ampex Company of nearby Redwood City. We lost the first two-and-a-half hours of a three-hour session trying to get tape machines to record up to speed. In the last half-hour the engineer decided to return to the standard procedure of cutting directly on acetate.

Almost out of time, we recorded as fast as we could. Four sides, one take each. “Blue Moon,” Tea for Two”, “Laura” and “Indiana”. They were released in1949 by Coronet Records, a local label owned by the Dixieland trombonist Jack Sheedy. “Blue Moon” was chosen “Record of the Month” and cited as a polytonal experiment by Metronome magazine, an important jazz publication of the period. These masters were subsequently purchased for a few hundred dollars, and the Fantasy jazz label was begun. That so much could happen from those first four sides is a miracle considering the circumstances in which they were recorded.

A few months before the Coronet session I had gone with a friend to a studio in San Francisco and made my first unofficial solo piano recording. The friend, O. Basil Johns (the “O” stands for Original), encouraged me so much that I insisted that he attend every recording session thereafter. I could look up and take heart from the smiling face behind the glass of the engineer’s booth. When the Quartet began to record albums in New York he was sorely missed. (Thirty years later Basil was on hand to repeat history. His enthusiastic shout can be heard on my most recent album on the track “Home Town Blues” recorded live at the 1979 Concord Jazz Festival.) He was also present for the first Fantasy recording session, when Cal Tjader switched to bongos. “Body and Soul” and “That Old Black Magic” came from that 1950 session. He was still smiling in approval when Cal moved to vibes and we established the sound that made us immediately identifiable as the Dave Brubeck Trio.

The Octet 1950 (left to right) Bill Smith, Paul Desmond,

The Octet 1950 (left to right) Bill Smith, Paul Desmond, Dave Van Kriedt, Cal Tjader, Ron Crotty,

Dick Collins, Bob Collins, and Dave Brubeck.

Brubeck Collection,

Holt-Atherton Special Collections,

University of the Pacific Library.

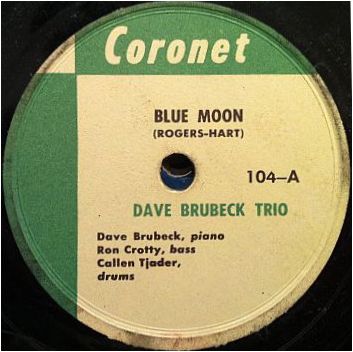

The Octet, which predated and spawned the Trio, was not recorded until the initial Fantasy investment had been recovered. Just as on our tours the fee for one engagement paid for transportation to the next, so on our “little” record label one album had to subsidize the next. The experimental compositions by members of the Octet date back to 1946 but we decided that our first release should showcase a series of arrangements, lavish in the use of counterpoint and polyrhythms, with a Picasso-style portrait of the Octet by Original Basil Johns on the cover. With one exception, “Closing Theme”, all tracks are from this 1950 session.

Fantasy 3-3 Dave Brubeck Octet

Fantasy 3-3 Dave Brubeck Octet

The Octet personnel varied occasionally, depending on who had taken a temporary job with another band. But the nucleus of the group was Dave Van Kriedt (tenor saxophone), Bill Smith (clarinet), Dick Collins (trumpet), Jack Weeks (string bass) and I. All of us were composition students of the French composer, Darius Milhaud, at Mills College in Oakland, Calif. Paul Desmond, who used to “sit in” with us when I worked with the “3 Ds” at the Geary Cellar in San Francisco, was recruited to fill the alto chair, and Dick Collins, brother, Bob, played trombone. Jack Weeks would move from trombone to bass, depending on what was needed to fill out the band. We had several drummers, finally ending up with Cal Tjader, whose versatility later proved so valuable in the Trio.

Organized originally as a rehearsal group in order to hear our own compositions, we were so encouraged by the student response to a benefit concert for Mills scholarships that we decided to try for bookings as “The Eight”. Failing that, we resolved to work in smaller groups from within the band. ‘Whoever got the job was leader for the night. We had very little work! We played a few Union Trust Fund concerts in libraries and twice made the trek up to Stockton to play at the College of the Pacific, where I had graduated from a few years before. We were a cooperative and shared the poverty equally. However, because of my long stint at the Geary Cellar, my name was better known, and for our first full-fledged public concert in 1949 at the San Francisco Marine Memorial Auditorium the promoter, Ray Gorum, insisted that “The Eight” be billed as the "Dave Brubeck Octet".

Dave Brubeck & Jimmy Lyons

Dave Brubeck & Jimmy Lyons Jimmy Lyons, who is now General Manager of the Monterey Jazz Festival, was a popular KNBC late-night disc jockey at the time, and we invited him to act as master of ceremonies. Jimmy was so taken by the originality of the group that he started an enthusiastic crusade on our behalf and arranged an audition at NBC. We wrote special material for our audition, some of which appeared on the Octet’s second release. The radio show didn’t materialize, but Jimmy continued to tout us to other musicians, to their managers and to record company representatives who passed through town. It was he who arranged for us to open a Woody Herman concert at the San Francisco Opera House.

I can’t remember now how we were received. Tolerated, I suppose. After all, my own father had described one of our concerts at the College of the Pacific as “the damnedest bunch of noise” he’d ever heard. But I do remember Woody’s band listening behind the stage curtain and our surprise when we emerged from the orchestra pit to their applause. Coincidentally, just in the past year, the Dave Brubeck Quartet has played three concerts followed by Woody’s youthful band; and each time my mind has raced back to that concert 30 years ago when everything seemed to ride on our acceptance.

And, gradually, it came. Musicians first. The two Charleses- Mingus and Parker - came to San Francisco to “check us out" they said. Stan Kenton asked me to write something for his band. Then the jazz journalists. Barry Ulanov had heard the Trio and wrote about us in Metronome. In 1956, in the album notes for an Octet reissue, I wrote: “Probably the first mention of Paul Desmond, Dick Collins or me in any trade paper came after Barry Ulanov’s visit in l949. George Shearing and Duke Ellington heard and helped spread the word. The faint beginnings of a West Coast renaissance in jazz was beginning to be felt. But too late for the survival of the Octet.

When I decided to form a group that would be more economically feasible, my logical choice for drummer was Cal Tjader. Ron Crotty, who attended San Francisco State College with Cal, joined us on bass. I had the idea that once a trio was established I would go back to the Octet by adding as many horns as the budget would allow. And, in fact, I occasionally did that for some engagements in San Francisco. The Trio’s first club job was at the Burma Lounge near Lake Merritt in Oakland, and over the next six months we became the favorite jazz hangout for university students, one of whom was Carl Jefferson, founder of Concord Jazz Records.

Jimmy Lyons played our recordings on his late-night show, and on the strength of the initial response to those airings, he persuaded the KNBC program director, Paul Speegle, to give us a 15 minute once-a-week show. “Lyons Busy” as the program was called, could be heard the length of the West Coast and far beyond Hawaii into the Pacific. Many young people in the military who heard our broadcasts would subsequently come to see us when they passed through San Francisco.

Having to come up with new material for each show quickly expanded our repertoire. In the club we could improvise as many choruses as we wanted, and Cal, who was just learning vibes, developed rapidly as a soloist. But for radio and recordings we were pretty much limited to the standard three minutes, which demanded from us some intricate arrangements and less reliance on the long improvisations that would later characterize the Quartet. “Singin’ in the Rain” and “Undecided", two such tight arrangements with improvised choruses, were listed among the best records of the year 1950 in Metronomes Year book – Jazz ’51.

.jpg) A number of the Trio’s early 78s were put on one LP in February l952, and the late Ralph J. Gleason, jazz critic and columnist for the San Francisco Examiner at the time, summarized in the album notes the Trio’s ascendancy:

A number of the Trio’s early 78s were put on one LP in February l952, and the late Ralph J. Gleason, jazz critic and columnist for the San Francisco Examiner at the time, summarized in the album notes the Trio’s ascendancy:

“In the short space of two years, Dave Brubeck has risen from the obscurity of an unknown jazz pianist to a point where he is accepted in this country and abroad as one of the leaders of the modem school of musicians.

After reviewing his Trio and Octet records, Metronome picked him for its “Small Band of the Year” award. His group placed fifth in the Downbeat poll, led only by the George Shearing, Charlie Ventura, Red Norvo and Louis Armstrong groups”.

In the summer of 1949, there was a group of San Francisco musicians calling themselves the “Jazz Workshop” or “The Eight’ who were interested in modem sounds. The pianist had something of the prophet in him, something of the teacher, and it was his articulate expression of their musical ideas that brought the Trio into being. Now less than three years later, Dave is so far in the vanguard of the young moderns that critic John Hammond, writing in the New York Daily Compass, calls him “a new figure in jazz to whom the terms ’progressive’ and 'radical’ may justly be applied - a brilliant technician, a trailblazer in music, uncompromising in his standards. Although his music is cerebral, it has tremendous drive and surprising warmth.

Metronome editor Barry Ulanov in a recent issue wrote:

“Dave’s success was and is inevitable. More than most jazz musicians, he has the equipment for both commercial and musical success. He communicates his ideas through a series of levels - melodic, harmonic, rhythmic - that may escape the technical comprehension of his listeners, but rarely eludes their more easily given responses, emotional and intellectual. Perhaps the best word to sum up Dave Brubeck’s music is ‘legitimate’. It is certainly a better word than ‘classical’, which suggests a tie to traditional music stronger than Dave’s actually is, for the core of his contribution is a disciplined employment of all the musical devices which make sense in jazz, whatever their source. In that employment Dave has broadened jazz just a little more and given jazz another badly needed large voice”.

Nevertheless, I felt more like an irrelevant small voice in the brash real world. The Trio continued to play in small clubs, and we drove from San Francisco to Los Angeles to Salt Lake City, Portland, Seattle and east to Chicago with bass, drums, vibes and the three of us squeezed into my old Kaiser Vagabond. By the spring of 1951, Jack Weeks from the Octet had replaced Ron Crotty on bass while Ron served his compulsory military time. For several months the Trio was booked into the Zebra Room in Honolulu. My wife and children had come over with the band, and we rented a small apartment near Waikiki. One afternoon, while demonstrating to my two small sons how to dive through a wave, I hit a sand bar. It almost ended everything. It did end the Trio.

My recovery was a long ordeal. Cal and Jack returned to the mainland and started their own group with another pianist. Jimmy Lyons gave progress reports about my recovery on his radio broadcasts, and I received cards and letters from listeners urging me to get well and return to San Francisco. There was even an anonymous gift in my bank account, which allowed us to take a ship home, since I was not yet permitted to fly.

The Black Hawk, San Francisco’s new jazz club, assured me a job when I was able to work again. From Tripler Hospital I wrote to Paul Desmond telling him “to line up” bass and drums so that we could form that quartet we had so often talked about. Thus, in the summer of 1951, as the result of an accident, began the long and rather amazing life of the Dave Brubeck Quartet with Paul Desmond. But my association with Paul had dated back long before that, and even before the Octet. In 1944, through the urging of Dave Van Kriedt, who had roomed with me at the College of the Pacific, I had gone to the Presidio in San Francisco, where Dave Van Kriedt and Paul Desmond were stationed, to audition for the Presidio jazz band. Paul described me at our first meeting as looking like “a surly Sioux’. He said we agreed to play the blues in G and I opened with a B-flat chord in one hand and a G chord in the other, and, “having never heard of polytonality, much less played in two keys at once” he concluded that “this man is stark raving mad”. I didn’t see Paul again until I had returned from overseas at the end of World War II.

While studying at Mills, I took a job in San Francisco with Darrell Cutler, a tenor player, who had been in my big band in college, and Don Ratto, also from Stockton. The “3 Ds” (Darrell, Don and Dave), as we were called, were often joined by a brilliant young altoist who was studying to be a writer, Paul Breitenfeld. (His name change to Desmond came later.).jpg) Paul and I seemed to have some kind of telepathic communication. We could anticipate each other’s thoughts to the uncanny extent that we would even make the same mistake together, and then correct it, in the same way, together. We seemed able to spin out contrapuntal lines anticipating each other’s thoughts. If any two musicians were destined to play together, it was Desmond and l. When Paul found a weekend job for us at the Band Box down the Peninsula, near Stanford University, I quit the six nights a week with the “3 Ds” to join the Paul Desmond Quartet, thereby cutting my already meager income in half. In a few weeks the job ended. Paul and the bass player, Norman Bates, who would be part of a later Quartet, went to a summer resort job, and I was stranded. That’s when I determined to form a trio.

Paul and I seemed to have some kind of telepathic communication. We could anticipate each other’s thoughts to the uncanny extent that we would even make the same mistake together, and then correct it, in the same way, together. We seemed able to spin out contrapuntal lines anticipating each other’s thoughts. If any two musicians were destined to play together, it was Desmond and l. When Paul found a weekend job for us at the Band Box down the Peninsula, near Stanford University, I quit the six nights a week with the “3 Ds” to join the Paul Desmond Quartet, thereby cutting my already meager income in half. In a few weeks the job ended. Paul and the bass player, Norman Bates, who would be part of a later Quartet, went to a summer resort job, and I was stranded. That’s when I determined to form a trio.

Paul was on the road with either the Jack Fina or the Alvino Ray band when he heard the first Trio recordings. By the time he came off the road, the Trio had moved from Oakland over to the Black Hawk, which had become a thriving jazz mecca. Paul “sat in” with us whenever he could and even followed us to Los Angeles to play, though we were only earning union scale for three musicians. We talked about forming a quartet, but by then the Trio was developing a following, and it seemed too soon to add another instrument to the group that had lust been named “Small Band of the Year’.

Even after the Quartet was formed, we met some resistance to the idea of a horn. In fact, when the Dave Brubeck Quartet showed up in Los Angeles, the club owner actually asked me to send Paul home. He wanted the Trio that he had heard on record and had hired before my accident. And Leonard Feather, reviewing the Quartet’s first New York appearance at Birdland, wrote: “lt lacked the compactness of the Trio, and of the Octet, both of which had led us, via Fantasy records, to look for something a little more exciting”.

Paul Desmond, Heb Barman, Dave Brubeck

Paul Desmond, Heb Barman, Dave Brubeck & Wyatt "Bull" Ruther

But the jazz audience had different ideas. Although the Quartet with Paul was not an automatic success, I think that two of the tracks included in this collection-“Look for the Silver Lining” and “This Can’t Be Love” - will convince you that it should have been. They were taken from a broadcast made at the Surf Club in Hollywood only a few months after the group was formed and within the first week of Wyatt Ruther’s joining us on bass. An even earlier Quartet example is “A Foggy Day” with Freddie Dutton on bassoon and bass, recorded during our “break in” period at the Black Hawk. Herb Barman is the powerful drummer on all three tracks.

By 1952, Lloyd Davis, who was a classically trained percussionist and who now plays with the San Francisco Symphony, had replaced Barman, and on the record he can be heard playing softly behind Paul and me on “Over the Rainbow”, “You Go to My Head” and “Give a Little ‘Whistle” -three of Paul’s all-time favorites. After Paul and I had made our duet album for Horizon (1975), he asked me to listen again to the1952 Storyville album, which he had rediscovered during his recent illness. He wanted to make another duet recording more reminiscent of Storyville. Unfortunately, Paul’s death came too soon for us to realize this idea.

The empathy between Paul and me is nowhere more evident than on these early self-exploratory improvisations, recorded in George Wein’s nearly empty Storyville Club in Boston on a Sunday afternoon. Developing an idea that Paul had alluded to in the conclusion of his choruses, I improvised a theme on “Over the Rainbow” that I liked so well I later wrote it down. Entitled “Summer Song” it was recorded by the Quartet on Jazz Impressions Of The U.S.A. and by Louis Armstrong as a vocal in “The Real Ambassadors”.

The “Jazz at Storyville” LP holds many great memories for me because it was recorded during that exciting building period when we were being discovered by others (George Wein, Charlie Bourgeois and Nat Hentoff are all associated with this album) and when we were also discovering for ourselves a potential for emotional communication.

“Star Dust” is another track typical of this period, when Paul and I concentrated on standards but so transformed them that only a harmonic detective could ferret out the tune, except for a few measures when the melody is stated, in this case, in the closing bars. “Creation” was our credo, and we seldom relied on arrangements. Occasionally, as with “Lulu’s Back in Town”, we would decide on an approach - in this case, contrapuntal - and try to develop it. “The Trolley Song", which was originally released with my voice rehearsing the rhythm section (Ron Crotty and Lloyd Davis), falls into the category of an “agreed upon” approach, which was rhythmic, leaving everything else up to Paul and me to improvise. That’s why I think it was difficult to put us into a category even though some journalists tried by labeling us “West Coast” or “cool”. Barry Ulanov, in his notes for the album from which “Star Dust” and “Lulu” came’ wrote:

“Dave’s identity is in his diversity" I believe this. I’ve never wanted to be trapped into a particular style that wouldn’t allow for the expression of the whole range of human emotion and an awareness of the entire history of jazz.

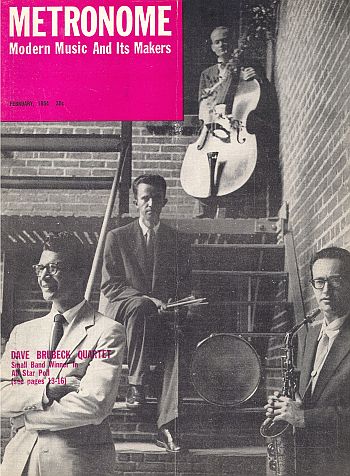

Metronome Poll Winners, Dave Brubeck, Lloyd Davis,

Metronome Poll Winners, Dave Brubeck, Lloyd Davis,Ron Crotty & Paul Desmond

Starting in 1953, the Dave Brubeck Quartet received many awards, including first place in both the critics’ and the readers’ polls conducted by Downbeat magazine. We were signed by Columbia Records, and in 1954, we were the subject of a Time magazine cover story. But these “Pre-Columbian” recordings from 1951- 1953, reflect, I think, a most exciting period in our development, before we were well known to the world at large.

The solo selections were recorded in 1956 at my new home in the hills overlooking the bay in Oakland, California. The notes for the solo album were written by the late Russ Wilson, a veteran journalist and jazz columnist for the Oakland Tribune. I can add very little to his commentary about the individual tunes:

“Sweet Cleo Brown”: This, in a sense, is a monument erected to an individual and to a remembrance of things past. Cleo Brown was born in Mississippi in 1909 and reared in Chicago. In 1935 Cleo made a series of sides for Decca with a rhythm section, which included Gene Krupa. The next few years are obscure, but in 1941, after a long illness, which finally led to her hospitalization in Stockton, Cleo resumed her career at a club in this central California city. The intermission pianist was a 20-year-old College of the Pacific student, Dave Brubeck.

When I heard Art Tatum for the first time, I brought a note of introduction from Cleo. Art asked about her health and about how she was playing. “Oh, she’s great!” I replied. “She must have the fastest left hand in the world”. “Sit here”, said Tatum, positioning me at the bar, where I could have an unobstructed view of the keyboard. Unbelievably, I was the only customer in the joint. Tatum went to the piano and proceeded to play with his left hand only, swinging with impeccable technique while holding his right hand aloft, just to be sure that I would make no mistake as to where all those notes were coming from. So I’ll concede that Cleo Brown had perhaps the second- fastest left hand in the world.

“I’m Old Fashioned” and “They Say It’s Wonderful” are two of those “old-fashioned” and “wonderful” standards that I’ve played behind singers and always wanted to develop on my own. Frances Lynne used to sing “I’m Old Fashioned” as a tender ballad with the “3 Ds” at the Geary Cellar. This tune is associated in my mind with her. Frannie left San Francisco to sing with Gene Krupa, and Charlie Barnet, and when I last saw her in san Francisco a few years ago she was looking as beautiful as ever and was married to trumpet player Johnny Coppola, who used to be with Woody Herman.

Of “They Say It’s’ Wonderful" Russ Wilson wrote:

This wild and wonderful up tempo swinger was included at my insistence. I argued that besides its intrinsic merits, it displays a facet of Dave’s solo work which is largely unknown. I liked its polyrhythmic structure, but Dave had rejected it as uneven in quality.

My favorite solo track is “Imagination". Incidentally, I used to know the lyrics to almost every song in the jazz library, and sometimes I keep the words in mind during my choruses, playing upon them as well as on the musical elements of a song. The syllabification of the months I was in Australia, where I saw Dave Van Kriedt, whose word i-mag-i-na-tion forms an introduction, and using free association, the subconscious mind takes over the direction of the improvisation – an approach not often used by solo pianists in the ‘50’s.

The work represented here, recorded when I was between 22 and 35, perhaps reveals more about me and the shape of things to come than any other single collection. There are other anthologies that include the work of Joe Dodge on drums and Norman Bates on bass. Although they joined the Quartet later, my association with them was established during the same time period covered in these releases.

To verify images and personnel, I’ve gone through old press clippings, ledger books, album covers and diaries and stirred up memories of musicians I worked with in the late '40’s and '50’s. Many are still my closest friends. In the past few months, I was in Australia where I saw Dave Van Kriedt whose “Fugue on Bop Themes” remains a classic, taught in classrooms as a fine example of contemporary fugue. Recently I was playing concerts with Bill Smith in France and also in the Pacific Northwest, where he teaches at the University of Washington. From the time I first knew Bill, when he was 18, he has been at the forefront of the avant-garde. If there is any one dominating force in those “Pre-Columbian” years, besides the influence of Darius Milhaud and Duke Ellington, it was my association with the wonderfully talented musicians on the scene in San Francisco at that time. This collection is dedicated to them.

Data of Box Set release

Tracks

Side One: The Dave Brubeck Octet

The Way You Look Tonight

Love Walked In What Is This Thing Called Love

What Is This Thing Called Love

September In The Rain

Prelude

Fugue On Bop Themes

Let’s Fall In Love

IPCA

Closing Theme

Side Two: The Dave Brubeck Trio

Indiana

Blue Moon

Tea For Two

Laura

That Old Black Magic

Sweet Georgia Brown

Let’s Fall In Love

Side Three: The Dave Brubeck Trio

Avalon

Singin’ In The Rain

Squeeze Me

Always

Wonderful

Body And Soul

Too Marvelous For Words

Side Four: The Dave Brubeck Quartet

Give A Little Whistle

You Go To My Head

Over The Rainbow

This Can’t Be Love

Side Five: The Dave Brubeck Quartet

Lulu’s Back In Town

A Foggy Day

Star Dust

The Trolley Song

Look For The Silver Lining

Side Six: Dave Brubeck Solo Piano

Sweet Cleo Brown

I’m Old Fashioned

Imagination

They Say It’s Wonderful

The box set, consisting of 3 LP’s was issued as a “Book Of The Month – Records - Club Selection” in 1980. The tracks and their sequence were selected by Dave. The box set includes a wonderful 14- page booklet outlining the tracks selected, great photographs, a biography of Dave and the essay included here written by Dave titled "How It All Happened".

Unfortunately this release has never been issued on CD.

Personnel Dave Brubeck

Dave Brubeck

Herb Barman

Bob Bates

Bob Collins

Dick Collins

Ron Crotty

Bob Cummings

Lloyd Davis

Paul Desmond

Joe Dodge

Fred Dutton

Wyatt Ruther

Bill Smith

Cal Tjader

Dave VanKriedt

.jpg) Cal Tjader, Ron Crotty & Dave Brubeck

Cal Tjader, Ron Crotty & Dave Brubeck Dave & Paul, Storyville, 1954

Dave & Paul, Storyville, 1954 Don Ratto, Frances Lynne,

Don Ratto, Frances Lynne,