.jpg)

Iola Brubeck - The Writer

As noted in the section Iola's Role, Iola Brubeck (right with Dave - copyright Brubeck Family) was a gifted lyricist. A lesser known fact is that she was also a gifted writer. Iola initiated, wrote much of and co-ordinated the wonderful Dave Brubeck Newsletter, which was distributed to fans for several decades.

As noted in the section Iola's Role, Iola Brubeck (right with Dave - copyright Brubeck Family) was a gifted lyricist. A lesser known fact is that she was also a gifted writer. Iola initiated, wrote much of and co-ordinated the wonderful Dave Brubeck Newsletter, which was distributed to fans for several decades.

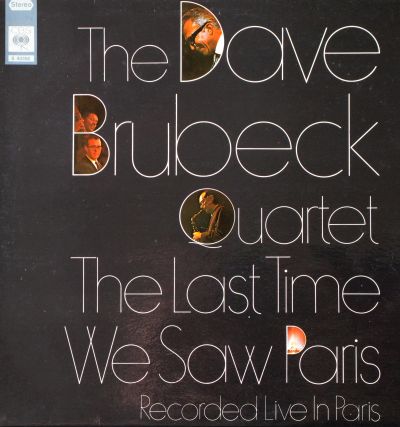

She also on one occasion wrote the liner notes for one of Dave's Columbia releases - The Last Time We Saw Paris which clearly demonstrated her writing prowess. These are reproduced below.

Liner Notes - The Last Time We Saw Paris - Copyright Columbia Records ©

The last time we saw Paris was in the autumn of ‘67. On November 13 at Salle Pleyel, The Dave Brubeck Quartet played its final performance in Europe.

As all the posters used to say: THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET, featuring PAUL DESMOND, with JOE MORELLO and GENE WRIGHT (he prefers Eugene, but it never seemed to come out that way) developed into an institution across America and around the world. Scarcely a day goes by that the mail does not bring a letter from Djakarta, or Melbourne, or Warsaw, or Possum Trot, Texas.

As all the posters used to say: THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET, featuring PAUL DESMOND, with JOE MORELLO and GENE WRIGHT (he prefers Eugene, but it never seemed to come out that way) developed into an institution across America and around the world. Scarcely a day goes by that the mail does not bring a letter from Djakarta, or Melbourne, or Warsaw, or Possum Trot, Texas.

If The Dave Brubeck Quartet was a symbol of the postwar era to the jazz-conscious under-forty population, to those of us who were intimately involved with the growth of the Quartet, it had become a way of life. Although we all knew that it had to come to an end someday, that someday was always in our minds as an intangible tomorrow. The realization that the 1967 tour was actually to be the last in Europe dawned slowly.

Members of the Quartet had known for a year that the group would disband at the end of 1967, but no public announcement had been made; and it had been a fairly successful trade secret. However, Paul, in an interview at the Newport Jazz Festival, had intimated that a parting of the ways might be imminent and the rumor had preceded the Quartet to England, where the tour opened with two concerts at the Royal Festival Hall. Although Dave had asked specifically that the publicity for their appearances in Britain and on the Continent not be labeled as a “farewell tour,” the unofficial word spread so quickly that every hall throughout the twenty-two concerts in England and Europe was jammed with sentimental, devoted fans who came to hear Gene, Joe, Paul and Dave together for the last time.

When I joined Dave in Ireland, before going on to the Continent, he told me the Quartet had never played better, nor seemed to communicate so well. On surface, the prevailing mood seemed to be the same as it had been on every tour for the past decade. Those four men, who were such a remarkable unity on stage, each lived within his own world. There was Eugene—always the first man on the band bus. The first musician at the hall, silent until he began to greet the innumerable “cousins” and “adopted sons and daughters” with whom he had kept a postcard correspondence over the years. There was Joe, and his wife Jean—greeted in each new town by still another representative from that mysterious society of drummers, engaged in continuous conversations about the secrets of Joe’s art, paradiddle, exercise and hardware.

There was Paul—pockets bulging with paperbacks (he usually reads two or three simultaneously), sizing up each city and in twenty-four hours knowing more about its hangouts and hang-ups than a native would learn in a lifetime. There was Dave—carrying his oversized briefcase, a puzzle to customs inspectors until they saw its harmless contents of huge sheets of score paper clipped to an easel. Every spare moment, in terminal waiting rooms, on planes, in the band bus, was involved in orchestrating his oratorio, “The Light in the Wilderness” which was to be premiered early in ‘68. All of this was part of the normal picture. Dave was usually involved in a project outside of the Quartet that consumed all the time and energy not spent upon the stage. Paul was usually involved in his research for a bachelor’s guide to Europe and was our only reliable source of information as to where to eat and what to see on a rare night off. Joe was usually the center of a covey of drummers, and Gene usually practiced, wrote letters and quietly “took care of business,” seeing that the tour ran smoothly. But there were invisible differences and this was apparent when they began to play.

As I sat in the audience, concert after concert. I could sense a growing inner excitement within the musicians. Each night their performance seemed to get better, the standing ovations to last longer, and the audience involvement go deeper.

Reading the reviews as we flew to the next engagerment, the tour began to take on the unreal quality of a screenplay for an Alice Faye musical, complete with montage of success headlines flashed against a background of clickety-clacking train wheels. Dusseldorf! ... Munich!....Frankfurt! (Wow, Frankfurt! What a memorable night for the Quartet and the audience.)... Hamburg! . . .Vienna! …(Here the spell was almost broken. Paul became ill in Hamburg and Dave, Joe and Gene had to play two concerts as a trio to packed houses in Vienna. They had never performed in this music capital of Europe and were under tremendous pressure to produce, which they did triumphantly!)... and, now... Paris!

Paul flew from Hamburg, still shaky, and met us at Oily airport. It was a relief to know that he had made it. There was only a brief time to rest and reflect at the hotel before going to the concert hall. We were drawing close to the end of the tour. Back home there were a few scattered college dates left to play on the East Coast and in the Midwest, some of which would be recorded. Dave decided to make an official announcement about the disbanding of the group when those concerts were completed but until that time the aim was to get better and better, to define over and over for himself, the Quartet and the listener, what The Dave Brubeck Quartet was all about.

Those of us who have followed the Quartet over the years will recognize that the reading of the list of tunes recorded that night in Paris does not, by any means, reveal the contents of the album. Swanee River in Paris is a far cry from the studio version that was recorded for the album ‘Gone With the Wind” in 1959. These Foolish Things has been a favorite of Paul and Dave for as long as I can remember. Actually, I think, it has been recorded by them only once, on a Fantasy album, “Jazz at Oberlin,” made in 1953. Forty Days was introduced on the Quartet’s fifteenth anniversary album, “Time In.” The theme has gone through an intensive developmental period and has been incorporated as a choral anthem as well as an improvisatory section of Dave’s oratorio. The performance in Paris reflects the concentration that has gone into the material and is an abstraction of the temptations of Jesus in the desert.

Those of us who have followed the Quartet over the years will recognize that the reading of the list of tunes recorded that night in Paris does not, by any means, reveal the contents of the album. Swanee River in Paris is a far cry from the studio version that was recorded for the album ‘Gone With the Wind” in 1959. These Foolish Things has been a favorite of Paul and Dave for as long as I can remember. Actually, I think, it has been recorded by them only once, on a Fantasy album, “Jazz at Oberlin,” made in 1953. Forty Days was introduced on the Quartet’s fifteenth anniversary album, “Time In.” The theme has gone through an intensive developmental period and has been incorporated as a choral anthem as well as an improvisatory section of Dave’s oratorio. The performance in Paris reflects the concentration that has gone into the material and is an abstraction of the temptations of Jesus in the desert.

The influence of the early pianist, Fats Wailer, to whom One Moment Worth Years was originally dedicated, is still apparent in Dave’s style, although this Paris version is quite distinct from Dave’s original solo piano recording, or the Quartet’s version of ten years ago. During the choruses of One Moment, one can hear quotes from many other tunes as Paul subtly relates his own private story to those who know the clues. Eugene takes a remarkable bass solo, and the intricacy of Joe’s exchange of fours is filled with typical humor.

Dave’s favorite tune from the “Bravo! Brubeck!” album, recorded in Mexico City in the spring of ‘67, is La Paloma Azul (The Blue Dove). It is a folk melody instantly recognized throughout Europe. This Paris version is unique because Joe played a different kind of cymbal beat which seemed to nudge everyone into a more jazzy feeling. To French audiences Three to Get Ready is as popular as “Take Five,” both of which appeared first on the now historic “Time Out” album. Claude Nougaro wrote and recorded lyrics for Three to Get Ready, so the song is popularly known in France as “Jazz et Java.” As a dramatic example of the refining process of a jazz group, I suggest you play the original Three to Get Ready from “Time Out” and contrast it with this performance, which glides so effortlessly over two bars of three, followed by two bars of four. Paul and Dave freed themselves from the bar lines and are often thinking in terms of fourteen beat phrases, so that we are not aware of the underlying rhythm pattern.

As I listen to THE LAST TIME WE SAW PARIS, the mental image of the audience at Salle Pleyel comes to mind as vividly as a photograph. One can feel as well as hear their presence on this recording of the Quartet’s ultimate performance in Europe. I use the word “ultimate” with full awareness. According to the Oxford dictionary, it means: 1. beyond which nothing is contemplated or intended. 2. that concludes a process, course of action, or series. B. the final point or result; the end.

And that says it.

Iola Brubeck