CNN, What The Tributes Missed

Dave Brubeck was taking a horse ride with his father one day when he saw something that would haunt him for the rest of his life.He was along on a cattle-buying trip with his father, Pete, a rancher in Northern California. Pete Brubeck asked an African-American cowboy who everyone called "Shine" to come over and greet his son.

Pete Brubeck then asked Shine to open his shirt. Brubeck, then only 6, watched as Shine unbuttoned his shirt to reveal a brand on his chest: He had been marked like cattle. Shine was the first black person Brubeck had ever seen. A furious Pete Brubeck told his son that "something like this never should happen again."

"It had an impact on me I'll never forget," Brubeck told journalist Hedrick Smith for a documentary called "Rediscovering Dave Brubeck."

"I thought, 'What can I do about this?' It's like my dad (was) telling me to do something about it."

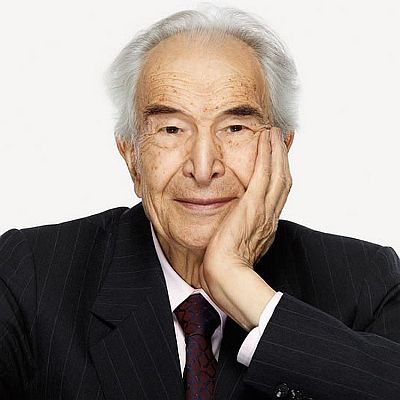

Brubeck, the pioneering jazz pianist who died this month at 91, did more to help people like Shine than most people realize. The tributes that poured in after his death tended to focus on the same themes: He was the jazz legend whose "Dave Brubeck Quartet" gave the world the jazz standard "Take Five," he stretched the boundaries of jazz and was a champion for civil rights.

Brubeck, though, was bigger than all of that. His life and music say more about this country's future than its past. He and an entire generation of white, black and Latino jazz musicians helped create one of the nation's first multicultural communities. They offered a snapshot of what this nation is becoming, like it or not.

To make that world possible, Brubeck and other white jazz musicians did something remarkable. They joined a jazz community where white men were the minority -- and whiteness was seen as a liability, not the norm.

How did Brubeck do it, and how did he thrive? Delve into his interviews and his music, and the clues emerge

Seeing genius in a 'servant'

He listened to the story of "the other."

Many fans know this story. Brubeck's breakout year came in 1954. He was touring with Duke Ellington, one of America's greatest composers and a jazz titan.

One day, Brubeck heard a knock on his hotel door. He opened it to find Ellington, smiling and holding several copies of Time magazine. Brubeck was on the cover. His heart sank. Ellington was his friend. He knew that Time had also been interviewing Ellington, and Brubeck thought the jazz composer deserved the honor over him.

"I wanted to be on the cover after Duke," Brubeck told the narrator in Ken Burns' epic documentary on jazz. "The worst thing that could have happened to me was that I was there before Duke, and he was delivering the news to me."

The black experience was initially foreign to Brubeck. He was born in Northern California and grew up on a cattle ranch near the Sierra Mountains. But even as his fame eclipsed many of his black musical mentors, he continually talked about the musical debt he owed to them.

The virtuosity of black artists like Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald sometimes did what a civil rights march or a court decision couldn't do -- force whites like Brubeck to see the humanity of black people.

One of the most famous jazz conversion stories comes from Ken Burns' "Jazz" documentary.

In 1931, Charles Black was a white teenager who decided to go hear Armstrong play in an Austin, Texas, hotel. He knew nothing about jazz, but something shifted in him as he watched a rapturous Armstrong perform.

"He was the first genius I'd ever seen," Black recalled. "It is impossible to underestimate the significance of a 16-year-old southern boy seeing genius for the first time in a black person. We literally never saw a black man in anything but a servant's capacity.

"Louis opened my eyes wide and put to me a choice: Blacks, the saying went, were 'all right in their place,' but what was the place of such a man, and of the people from which he sprung?"

Black would go on to join a team of lawyers that successfully convinced the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the segregation of students based on race in the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision.

An 'instinct for differences'

Brubeck was inspired by differences.

He didn't look like a jazz musician. When he led the quartet, he looked like a chemistry professor who accidentally found himself behind the piano. With his black horn-rimmed glasses, goofy grin and his square suits, the affable Brubeck looked like Mr. Normal.

Yet Brubeck was a wild man behind the keyboard. He was like a musical mad scientist -- combining unconventional time signatures and musical styles from other cultures that wouldn't appear to work but did.

He sought out the same combustible mix in his famous quartet. Many jazz leaders surrounded themselves with musicians who they had an almost telepathic rapport with onstage. But Brubeck's Quartet clashed.

Brubeck was known for pounding the piano with thunderous chords. His saxophonist, Paul Desmond, played with a light and lyrical style that was so exquisite that one critic said he left "a trail of honey in the air." And then there was his drummer, Joe Morello, a proud man with superb technique who wanted to be showcased more.

The group fought musically and personally. Morello clashed with Desmond. Desmond clashed with Brubeck. They were all so different, but Brubeck made it work.

He wasn't threatened by differences. They inspired him, said Ted Giola, a jazz historian and author.

"It's to Dave Brubeck's credit that he was able to hear these musicians that played very differently from him and was able to see that by taking them and getting their different sounds, he was adding, not subtracting," Giola said in the documentary "Rediscovering Dave Brubeck."

"Dave had an instinct for differences and how that was going to add to his music."

Jazz and democracy

It must be said, though, that the jazz world that Brubeck helped create wasn't a racial utopia.

Black artists were exploited. White audiences gravitated to some white jazz artists who didn't have the talent of black artists. Even some white artists like Brubeck were looked at with disdain by some black musicians.

Ian Carey, a jazz trumpeter who recently wrote an essay, "How Not to Become a Bitter White Jazz musician," said "white musicians unfairly profited from discrimination against black musicians by audiences and the music industry."

Yet Carey also said that when it came time to play, a lot of those divisions evaporated because of something inherent in jazz: Most jazz musicians don't care how you look. They just care about how you play.

"The bandstand is a great equalizer," he said. "You're going to get the best guy or woman for the gig. It doesn't matter what they look like."

Brubeck applied the same principle to his music. He led the first integrated band in the U.S. Army during World War II. He hired a black man, Eugene Wright, to be his quartet's bassist. The jazz world that Brubeck moved in was full of cross-racial and cross-cultural fertilizations.

They weren't just ahead of their time; in some respects, they were ahead of our time.

Some of the biggest jazz records came from artists who built friendships across racial and ethnic lines. The singer Frank Sinatra recorded with and relentlessly championed black artists like Fitzgerald and Count Basie.

The white saxophonist Stan Getz kicked off the bossa nova craze with his recordings with Brazilians Astrud and Joao Gilberto.

The jazz album classic "Kind of Blue" was spawned by the relationship between Bill Evans, a white, mild-mannered pianist who looked like a tax accountant, and the pugnacious black trumpeter Miles Davis.

Jazz lore says that initially some of the black members of Davis' band didn't want Evans to join the group because he was white, but Davis insisted because he loved Evans' "quiet fire."

"Kind of Blue" went on to become the best-selling jazz album of all time.

"He was a guy who looked like a stereotypical white nerd," Carey says of Evans. "But he could play. ... What he played was so much bigger than his appearance."

This egalitarian tradition in jazz -- everyone is equal on the bandstand -- has led some to compare it to democracy. The jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis once said that nothing captures the democratic process as perfectly as jazz.

"Jazz means working things out musically with other people. You have to listen to other musicians and play with them even if you don't agree with what they're playing. It teaches you the very opposite of racism and anti-Semitism. It teaches you that the world is big enough to accommodate us all."

Brubeck was a champion for democracy as well as jazz. It's often forgotten that many of the exotic rhythms he infused into his music came from tours his quartet took of the Middle and Far East. The State Department sponsored these tours to promote democracy during the Cold War.

Brubeck often compared jazz to democracy, saying both challenged individuals to express their freedom while being disciplined enough to respect the freedom of others.

Brubeck's words about jazz and democracy take on even more meaning with the recent presidential election.

It was a bruising election season and it revealed that the nation is experiencing profound demographic and social changes. Attitudes toward gay marriage are shifting, a black president was re-elected to a second term, and the U.S. Census Bureau predicts that the country will have a majority-minority population by 2043.

Perhaps some Americans feel like traditional jazz purists felt after they first heard Brubeck's exotic rhythms on his groundbreaking 1959 "Time Out" album: My world is changing, and I don't know these tunes.

David Simon, the creator of the HBO series, "The Wire," captured some of that angst in an essay he wrote right after the election entitled "Barack Obama and The Death of Normal."

"America will soon belong to the men and women -- white and black and Latino and Asian, Christian and Jew and Muslim and atheist, gay and straight -- who can walk into a room and accept with real comfort the sensation that they are in a world of certain difference, that there are no real majorities, only pluralities and coalitions."

"We are all the 'other' now," he wrote.

Brubeck entered that world over half-a-century ago.

He was a white man in a world dominated by black artists, but he wasn't threatened by the differences. He respected tradition but he wasn't afraid to subvert it if it meant growth. He learned how to listen to, and be inspired by the music of "the other."

Brubeck was often called the "Ambassador of the Cool," but he was more.

He was the ambassador for a new America