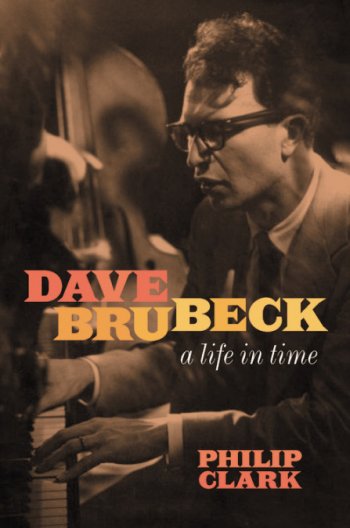

Dave Brubeck: A Life In Time

In February 2020, during Dave Brubeck's centennial, author Philip Clark launched his biography of Dave titled - Dave Brubeck: A Life In Time.

Press release by Da Capo publishing group.

The definitive, investigative biography of jazz legend Dave Brubeck (“Take Five”).

In 2003, music journalist Philip Clark was granted unparalleled access to jazz legend Dave Brubeck. Over the course of ten days, he shadowed the Dave Brubeck Quartet during their extended British tour, recording an epic interview with the bandleader. Brubeck opened up as never before, disclosing his unique approach to jazz; the heady days of his “classic” quartet in the 1950s-60s; hanging out with Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, and Miles Davis; and the many controversies that had dogged his 66-year-long career.

Alongside beloved figures like Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra, Brubeck’s music has achieved name recognition beyond jazz. But finding a convincing fit for Brubeck’s legacy, one that reconciles his mass popularity with his advanced musical technique, has proved largely elusive. In Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time, Clark provides us with a thoughtful, thorough, and long-overdue biography of an extraordinary man whose influence continues to inform and inspire musicians today.

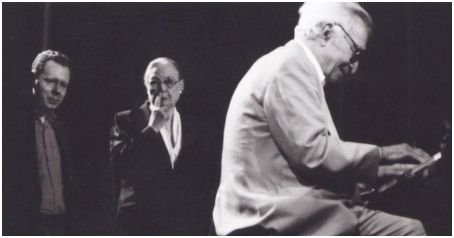

Structured around Clark’s ( pictured opposite at a pre concert sound check at Southend, UK, in 2003 with Dave and Iola Brubeck - image courtesy Bernie Rochester) extended interview and intensive new research, this book tells one of the last untold stories of jazz, unearthing the secret history of “Take Five” and many hitherto unknown aspects of Brubeck’s early career – and about his creative relationship with his star saxophonist Paul Desmond. Woven throughout are cameo appearances from a host of unlikely figures from Sting, Ray Manzarek of The Doors, and Keith Emerson, to John Cage, Leonard Bernstein, Harry Partch, and Edgard Varèse. Each chapter explores a different theme or aspect of Brubeck’s life and music, illuminating the core of his artistry and genius. To quote President Obama, as he awarded the musician with a Kennedy Center Honor: “You can’t understand America without understanding jazz, and you can’t understand jazz without understanding Dave Brubeck.”

Structured around Clark’s ( pictured opposite at a pre concert sound check at Southend, UK, in 2003 with Dave and Iola Brubeck - image courtesy Bernie Rochester) extended interview and intensive new research, this book tells one of the last untold stories of jazz, unearthing the secret history of “Take Five” and many hitherto unknown aspects of Brubeck’s early career – and about his creative relationship with his star saxophonist Paul Desmond. Woven throughout are cameo appearances from a host of unlikely figures from Sting, Ray Manzarek of The Doors, and Keith Emerson, to John Cage, Leonard Bernstein, Harry Partch, and Edgard Varèse. Each chapter explores a different theme or aspect of Brubeck’s life and music, illuminating the core of his artistry and genius. To quote President Obama, as he awarded the musician with a Kennedy Center Honor: “You can’t understand America without understanding jazz, and you can’t understand jazz without understanding Dave Brubeck.”

Reviews

Publishers Weekly

Music journalist Clark explores the life of composer and bandleader Dave Brubeck (1920–2012) in this concise but comprehensive biography. Culling from 10 days of interviews with the pianist in 2003, Clark analyses Brubeck’s music, citing the pianist’s “absorption in composition, the various ways in which composed music intersected with his unassailable belief in the urgency of improvisation, formed his approach to the piano—which became a laboratory in sound for this composer who improvised and improviser who composed.”

The author further explores Brubeck’s 1959 odd meter masterpiece in 5/4 time, “Take Five”; the equally complex “Blue Rondo la Turk” and “It’s a Raggedy Waltz”; and his innovative concept albums, including Time Out and Jazz Impressions of Eurasia. Clark details fascinating points from Brubeck’s life—including studying classical music with Darius Milhaud at Mills College, his time in the army, his refusal to play in the segregated South because his black bassist was not allowed to be on the same stage, and performing with his sons later in life.

Clark hits the right notes for die-hard Brubeck disciples and jazz neophytes alike.

The Guardian (UK)

In 1954 the pianist Dave Brubeck became the first jazz musician of the postwar generation to be featured on the cover of Time magazine, infuriating those who felt that this white middle-class Californian had no business taking the limelight from Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie or Thelonious Monk, the true pioneers of an essentially African American music.

In the decades that followed, Brubeck remained the focus of controversy, even as his quartet’s albums – with their abstract-expressionist cover art by Joan Miró, Franz Kline and Sam Francis – became almost as ubiquitous a fixture in the homes of the upwardly mobile as a hostess trolley or coffee percolator. By the dawn of the 1960s, when “Take Five”, a catchy little number in 5/4 time, was high in the pop charts, regularly requested on the BBC’s Sunday lunchtime radio show Two-Way Family Favourites, he was effectively the public face of modern jazz, even though his genial temperament and settled family life – he was married to the same woman for 70 years – ran contrary to what was generally seen as the idiom’s beatnik tendency.

For all the resentment he provoked, and the scorn poured on his sometimes heavy-handed playing, Brubeck was an interesting musician whose experiments with unorthodox time signatures helped open the way for others to venture beyond the standard 4/4 and waltz time. Combining his commitment to jazz with the lessons learned during his early studies with the expatriate French classical composer Darius Milhaud, he was happy to explore a hybrid work such as his brother Howard’s four-movement “Dialogues for Jazz Combo and Orchestra”, which he and his quartet recorded with the New York Philharmonic in 1960, under the baton of Leonard Bernstein. That earned him no points from the jazz purists, but their scepticism did not deter him from writing his own orchestral and choral pieces, some of them on sacred themes, later in life.

The British writer Philip Clark is not the first to attempt a Brubeck biography, but he is exceptional in leaving the details of his subject’s early life – a childhood that might have led to a career as a cattle rancher, for instance – until the final quarter of the book. That is because the author is after a looser, more discursive structure, examining the impulses behind Brubeck’s creativity through an approach freed from strict chronology, roaming backwards and forwards in his search for strands of development.

The first of his own encounters with Brubeck came in 1992, after a concert in Manchester, when he asked the artist to cast an eye over one of his own student compositions and received an encouraging response. A rapport was established and led Clark to accompany the quartet throughout a UK tour in 2003, continuing a dialogue maintained almost up to the pianist’s death, aged 91, in 2012. He supplements those conversations with material from Brubeck’s extensive personal archive, to which he was given access.

The bandleader’s early years and his rise from obscurity are closely examined, but the main focus of the story is inevitably the 10-year lifespan of Brubeck’s classic quartet, in which he and the alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, his long-term musical partner (and the composer of “Take Five”), were joined by the bassist Eugene Wright and the drummer Joe Morello. This was a perfectly balanced mechanism with an immediately identifiable sound, thanks largely to the ethereal purity of Desmond’s tone in the group’s foreground. Clark reveals that the musicians were subject to an unusual set of printed “principles and aims” in which Brubeck detailed their individual roles and responsibilities with a bracing and slightly alarming clarity.

In his laudable desire to enlighten and convince, Clark describes many of Brubeck’s piano solos in detail. The late Whitney Balliett of the New Yorker mastered the difficult skill of bringing an improvisation to life in the mind’s ear, largely by avoiding the use of technical terms. Clark shows no such reluctance, which means that readers unfamiliar with “polytonal chords” – a favourite Brubeckian device – may find themselves struggling, although the author’s sheer enthusiasm generally preserves the momentum. At a different level, Clark is sensitive to the musicians’ human characteristics, such as Desmond’s destructive ego and alcohol problems. He also deals fully with Brubeck’s insistence, at a time when segregation was still a de facto reality in some states of the US, on facing down the racism that resulted from the inclusion of Wright, an African American, in an otherwise all-white band (in 1959 he rejected his agent’s request to replace the bassist for a highly paid 25-date tour of southern colleges, cancelling the whole thing and forfeiting nearly $40,000).

For all his success, Brubeck was an essentially modest and unpretentious man whose immediate reaction to the Time magazine cover was that it should have gone to Duke Ellington. He once related, with some amusement, an enigmatic compliment paid to him by the great avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor: “He told me I was the missing link. He didn’t say between what and what.” Clark comes as close as anyone ever will to filling in the blanks.

The Observer (UK)

Their Take Five hit was the first jazz single to hit a million sales. It is the best-selling jazz single of all time. But previously unheard rehearsal tapes reveal that Dave Brubeck’s Take Five might never have been such a hit if he had stuck with an original version.

Philip Clark, author of a forthcoming book on Brubeck, the American jazz legend, has for the first time gained access to 1959 recordings that had lain forgotten in a Californian archive until now.

He was taken aback to hear a completely different rhythmic groove and Brubeck’s quartet struggling to make sense of it. “It sounds like a bad student jazz band,” he said. “Most notably, the fundamental rhythm is wrong. Nothing will knit together.” Take Five was the first jazz single to hit a million sales and such is its enduring popularity that a YouTube video of a 1966 performance has had more than 10 million views. But Clark believes that had the band kept with the earlier version, “Take Five would probably have disappeared”.

“It’s a completely different rhythmic feel,” he said. “They all really struggle with it and it never really works. [Joe] Morello, who was a miraculous drummer, can hardly play it. He keeps tripping over it and he can’t quite get it to fit into the groove.

“[Paul] Desmond is fiddling with the melody line, so there are bits where it’s in a minor key and suddenly goes into the major, and the transitions aren’t quite worked out. [Eugene] Wright is trying to work out his bass part, and Dave is desperately trying to glue the whole thing together. They try 12 times. Then Dave says let’s do another tune.

“After that all the rehearsal tapes are lost, so we don’t actually know what happened between the rehearsal and the rhythm we now know.”

Months after the tapes were recorded, Take Five was released in an altogether different form.

While the earlier version had been “much more driving and faster” with a lopsided Latin rhythm, this had a sexy 5/4 Take Five beat which “sits in the groove”, said Clark.

“Oom, chuck-a, chuck, boom, boom/Oom, chuck-a, chuck, boom, boom. No other instrumental jazz single has beaten its record. Time Out, the album on which Take Five appeared originally, went platinum in 2011, meaning sales of 2 million copies plus.” he added.

Brubeck, who died in 2012, was a pianist and composer who pushed jazz boundaries, experimenting with odd time signatures, improvised counterpoint, polyrhythm and polytonality.

But it is Desmond who is credited as Take Five’s composer. The quartet playing it was made up of Brubeck on the piano, Desmond on alto saxophone, Morello on drums and Wright on double bass.

Clark understands that the Brubeck estate might at some future date release the newly unearthed tapes – which cover around three hours of Time Out rehearsals.

In a further twist, the Take Five recordings contradicted what Brubeck had told him in extensive interviews in 2003, Clark revealed.

“Ninety per cent of what he told me about Take Five was completely undermined by the rehearsal tapes,” he said. “He insisted that the famous Take Five rhythms were in place at the beginning. Then I listened to the rehearsal tapes and the rhythm they were working with originally was unrecognisable.”

But he added that Brubeck had perhaps been misremembering a session that happened decades earlier.