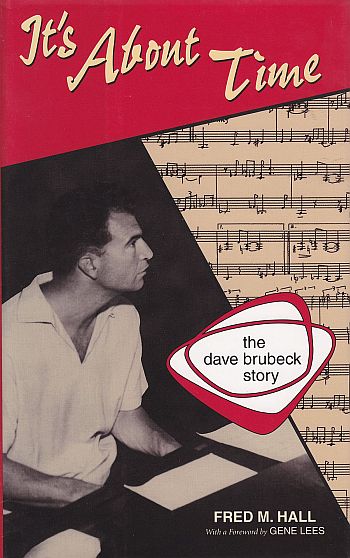

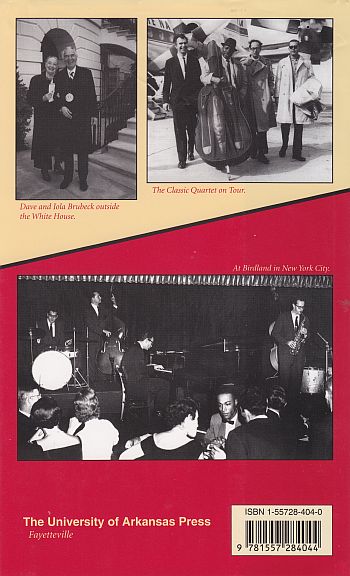

It's About Time: The Dave Brubeck Story

Fred Hall

Press Release 1996,University of Arkansas Press, 182 pages

Press Release 1996,University of Arkansas Press, 182 pages

A much-revered icon of jazz, Dave Brubeck, at seventy-five years of age, is still composing, recording, touring, and performing. He is, as Doug Ramsey calls him, "one of the most celebrated and successful jazz musicians of all time." It's About Time, Fred Hall's biography, explores the many influences on Brubeck's life and music: his youth on a cattle ranch in the foothills of the Sierras; a stint in Europe with Patton's army during World War II; the development of the West Coast jazz scene and the rise of the Dave Brubeck.

Reviews

Library Journal

Pianist and composer Dave Brubeck led a jazz quartet that produced the pop hit "Take Five" and achieved acclaim during the 1950s and 1960s. Hall, a veteran radio broadcaster, writes a fan's account of Brubeck's personal journey from boyhood up through international celebrity. Through interviews with Brubeck and others, we hear tales of "life on the road," meet Bru's peers, and learn something about his music, mostly about his later orchestral works. Questions about Brubeck's entire musical corpus and its place in jazz are better answered in Ilse Storb's Dave Brubeck: Improvisations and Compositions (Peter Lang, 1994). Hall's discography lists American-issued recordings but excludes the many European releases and reissues. Appropriate for general audiences.

Paul Baker, Univ. of Wisconsin, Madison (Copyright 1996 Reed Business Information, Inc)

Publishers Weekly

Publishers Weekly

Known for his fertile composing, frenetic time signatures and yen for experimentation, jazz artist Brubeck (now 75) has nonetheless had an upward struggle. His stylings were not in keeping with the times, and author Hall does a fine job of portraying Brubeck's plod from gig to gig in order to keep his ever-growing family afloat. Hall also nicely records Brubeck's struggles to “get his still evolving, polytonal, polyrhythm but not-bop music accepted in the jazz community and to make it part of the American musical mainstream.''

Brubeck's true artistry took some time to reach public recognition, and Hall takes the reader on a somewhat convoluted journey from the pianist's days as “a lanky, bright-eyed sixteen year old'' cowboy to days spent composing grand works with biblical themes. Hall introduces quite a menagerie of associates and hangers-on, such as Paul Desmond, Brubeck's musical partner who inexplicably deserted him at the most inopportune times, and eldest son Darius, a musical prodigy in his own right.

But the biography is arranged by topic, not timeline, and so the narrative makes long chronological jumps, particularly in the later chapters. While Hall has an eye for telling detail (Brubeck ate cornflakes and canned peaches for days on end and now can't stand the stuff), he does not have an ear for the revealing quote. Interviews with the artist and his wife fail to make Brubeck's life come alive to the reader. More often than not, the author traffics in the pedestrian rather than the controversial.

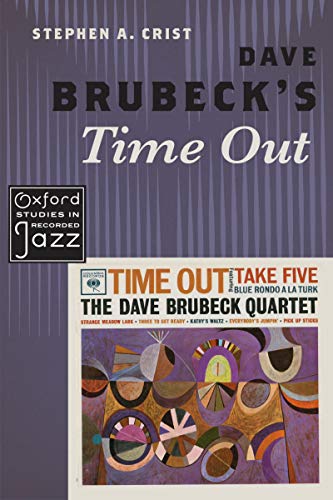

Dave Brubeck's Time Out (Oxford Studies in Recorded Jazz)

September 30, 2019

Stephen A. Crist (Author)

Notes on Amazon website. Dave Brubeck's Time Out ranks among the most popular, successful, and influential jazz albums of all time. Released by Columbia in 1959, alongside such other landmark albums as Miles Davis's Kind of Blue and Charles Mingus's Mingus Ah Um, Time Out became one of the first jazz albums to be certified platinum, while its featured track, "Take Five," became the best-selling jazz single of the twentieth century, surpassing one million copies. In addition to its commercial successes, the album is widely recognized as a pioneering endeavor into the use of odd meters in jazz. With its opening track "Blue Rondo à la Turk" written in 9/8, its hit single "Take Five" in 5/4, and equally innovative uses of the more common 3/4 and 4/4 meters on other tracks, Time Out has played an important role in the development of modern jazz.

Dave Brubeck's Time Out ranks among the most popular, successful, and influential jazz albums of all time. Released by Columbia in 1959, alongside such other landmark albums as Miles Davis's Kind of Blue and Charles Mingus's Mingus Ah Um, Time Out became one of the first jazz albums to be certified platinum, while its featured track, "Take Five," became the best-selling jazz single of the twentieth century, surpassing one million copies. In addition to its commercial successes, the album is widely recognized as a pioneering endeavor into the use of odd meters in jazz. With its opening track "Blue Rondo à la Turk" written in 9/8, its hit single "Take Five" in 5/4, and equally innovative uses of the more common 3/4 and 4/4 meters on other tracks, Time Out has played an important role in the development of modern jazz.

In this book, author Stephen A. Crist draws on nearly fifteen years of archival research to offer the most thorough examination to date of this seminal jazz album. Supplementing his research with interviews with key individuals, including Brubeck's widow Iola and daughter Catherine, as well as interviews conducted with Brubeck himself prior to his passing in 2012, Crist paints a complete picture of the album's origins, creation, and legacy. Couching careful analysis of each of the album's seven tracks within historical and cultural contexts, he offers fascinating insights into the composition and development of some of the album's best-known tunes. From Brubeck's 1958 State Department-sponsored tour, during which he first encountered the Turkish aksak rhythms that would form the basis of "Blue Rondo à la Turk," to the backstage jam session that planted the seeds for "Take Five," Crist sheds an exciting new light on one of the most significant albums in jazz history.

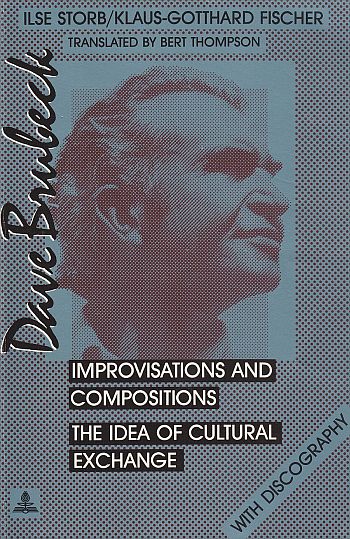

Dave Brubeck: Improvisations and Compositions,The Idea of Cultural Exchange

Authors: Ilse Storb, Klaus-Gotthard Fischer

Book synopsis

The pianist and composer Dave Brubeck represents the idea of cultural exchange as a basis for musical inter-cultural communication. He combines European concert music, as well as so-called non-European music, with acculturated jazz music. He also has a special interest in the integration of improvisation and composition. Occupying a large innovative space in Brubeck's sonoric harmonies are block chords, and, in the metric-rhythmic sphere, the time experiments with asymmetrical rhythms: “Essentially I'm a composer who plays the piano” (Brubeck).

The pianist and composer Dave Brubeck represents the idea of cultural exchange as a basis for musical inter-cultural communication. He combines European concert music, as well as so-called non-European music, with acculturated jazz music. He also has a special interest in the integration of improvisation and composition. Occupying a large innovative space in Brubeck's sonoric harmonies are block chords, and, in the metric-rhythmic sphere, the time experiments with asymmetrical rhythms: “Essentially I'm a composer who plays the piano” (Brubeck).

This book is a detailed survey of his improvisations, compositions and recordings.

The Authors:

Ilse Storb studied Music Education at the Cologne Conservatory as well as Musicology and Romance Languages at both the University of Cologne and the Sorbonne. She obtained her Ph.D. in 1966 researching Claude Debussy's piano music.

Professor Storb founded, together with Joe Viera, a “Jazz Lab” for music educators and authored a jazz book for schools. In 1982, she was appointed Professor of Systematic Musicology - including Jazz Research at the University of Duisburg. Ilse Storb has also organized three international conventions for jazz education and improvised music, produced a record with the members of the “Jazz Lab” and written a book about Louis Armstrong.

Klaus-Gotthard Fischer was born in Berlin 1939. He studied Physics at Bonn University and obtained his Ph.D. researching the theory of solid state magnetism. He is Director of the Center for Audio-visual Media at the University of Duisburg.

Reviews

Milhaud's student, Brubeck, was the only one who opened jazz to serious European composition techniques, and naturalized uneven metric forms into jazz. Ilse Storb's pioneering work, the first extensive portrayal of Brubeck's life and compositions, expounds the formal palette of his composing, cites numerous works unfamiliar to us (cantatas, oratorios), and contains, in addition, a professionally made discography compiled by Klaus-Gotthard Fischer. (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik)

Ilse Storb and Klaus-Gotthard Fischer have published an easily readable yet nevertheless academically grounded book about Brubeck and his music. (Radio Hessen 1990)

This book about the music of David Brubeck differs essentially from previous books published about jazz Musicians. Richly informative material and musical examples. (Jazz-Zeitung)

THE HARMONY OF DAVE BRUBECK Jack Reilly.

Includes CD of musical examples. Songs include:

Blues for All

Brandenburg Gate

The Duke

Her Name Is Nancy

Marble Arch

Thank You (Dziekuje)

The Waltz

When I Was Young

Reviews

Amazon

As Reilly did with Volumes 1 and 2 of The Harmony of Bill Evans , he now explores the harmony of Dave Brubeck through extensive writings, music examples, and audio examples as well. Fans of Brubeck and students of all jazz styles will find this in-depth exploration fascinating and informative.

Lynn René Bayley, Classical, Jazz & Ballet Critic, Fanfare magazine

Jack Reilly is one of the most creative yet lesser-known jazz pianists. I’ve never quite understood the reasons for his lack of visibility, except perhaps that he, like jazz singer Sheila Jordan, maintains a low profile because he refuses to compromise his talent. He won’t play show tunes, modern pop, fusion, or for that matter anything that smacks of populism. He goes his own way, plays what he wants, writes what he wants, and occasionally produces fine educational books on jazz theory such as this one as well as The Harmony of Bill Evans. As a friend and admirer of Evans since the early 1950s as a pupil of Lennie Tristano, Reilly remains fascinated and deeply involved in chords and chord structures as the basis of all the music he plays and/or writes.

Thus this book, although a tribute to Brubeck (who died as Reilly was putting the finishing touches on it), begins in Lesson 1, Polytonal Studies, with examples from his own La-No-Tib suite for piano and an explanation of its basic underlying principles. Reilly not only explains polytonality as a mechanism but, more importantly, how polytonality can be used as a medium of expression in both composition and improvisation. Of course there is always the danger, especially with younger and/or less experienced pianists, of becoming hooked on polytonality as a gimmick, meaning that the cleverness of writing bitonally or polytonally becomes the raison d’être of the music’s existence. Ironically, there was little chance of this happening back in the 1950s when Reilly (and Evans) first emerged, for the simple reason that polytonal and bitonal music was little understood by the general public and, for the most part, shunned. It took forceful individuals like Miles Davis, George Russell, John Coltrane, and Charles Mingus to keep at it until such point as it became part of the everyday lexicon of jazz improvisation and composing; and it is not coincidental that all four of those musicians played and recorded with Bill Evans.

As for Brubeck, he gets his due beginning with the second and longer section of the book, titled The Music. I was exceptionally pleased to see a major jazz improviser and composer like Reilly devote so much time to breaking down the structure as well as the harmonic relationships of so many Brubeck pieces. Reilly was extremely fortunate to have Brubeck himself help him analyze these structures via numerous phone conversations during his last year on earth, but the mere fact that this book exists and gives so much theoretical and critical analysis of Brubeck’s music is a minor miracle in itself.

Throughout the years when the Dave Brubeck Quartet was active, Brubeck himself often came under criticism or, worse yet, was completely dismissed by many jazz musicians (I won’t name names, but they know who they are) as a jazz pianist. He was often considered to be bombastic, heavy-handed, and unswinging. Many were the jazzmen who raved about his alto saxist, Paul Desmond, while dismissing Brubeck as a second-rate jazz player (some even had the audacity to ask Desmond to leave the quartet). Thus Reilly’s book restores Dave Brubeck to the place of prominence that I, and thousands of other fans who did understand music and knew he was good, knew that he rightly deserved and still deserves.

Reilly begins his analysis of Brubeck’s music with his very first composition, I Weep No More, written in 1945 in celebration of VE Day. Among the other pieces analyzed here are When I Was Young, The Waltz (with chord voicings by Reilly), The Duke, In Your Own Sweet Way, One Moment Worth Years, Her Name is Nancy, and several themes from the Eurasia suite: Nomad (Afghanistan), Brandenburg Gate (Germany), Dziekuje (Poland), Calcutta Blues (India), and Watusi Drums (Africa). How well I remember the backlash to that album when it came out! “That’s not jazz, it’s classical music…Why doesn’t Brubeck just go write suites and leave jazz alone?” etc. etc. (Yes, I’m paraphrasing. You won’t find these actual quotes on the Internet. But I heard them bandied about all the time back in the early 1960s.) Perhaps one reason why we, like Reilly, can come to appreciate this music so much better today is, to be frank about it, there’s a much better understanding now of jazz-classical fusion and the deep relationship between classical structure, or at least jazz structure based on classical principles, and “real” jazz as improvisation that is also based on classical music. (For the same reasons, such unusual early pieces as Red Norvo’s Dance of the Octopus, Morton Gould’s Boogie Woogie Etude, and even parts of Duke Ellington’s Black, Brown and Beige Suite are now considered great and important milestones in jazz, whereas in their own time they were not merely misunderstood but actively condemned as not being jazz at all.)

One of the more interesting of Reilly’s comments comes on pp. 45-46, when discussing In Your Own Sweet Way. To quote: “We’re definitely on slippery slopes in this tune. Section A can be analyzed as all in G minor or all in B-flat major. If you accept the G minor analysis, then the Roman numerals will be: Gm: II IV | I etc. And if you accept the B-flat analysis: VII IIIx7 | IV, etc. Does it matter? Yes and no! Yes, if you are a composer and want to understand major keys, their relative minors, and the use of secondary dominants…No, if you’re not so inclined to the intellectual/theoretical elements behind Dave’s thinking. See if I care!”

Yet there are many little insights scattered throughout this handy volume, and not just by Reilly. There are many anecdotes and sidelights written by Brubeck himself (would that Reilly had been lucky enough to get input from Bill Evans before he died!) and, on p. 66, comments by Brubeck’s son Darius, mother Elizabeth, and brother Howard on the pieces from the Eurasia suite. To be honest, I found these comments to be some of the greatest treasures of this collection and thus of interest even to the non-professional musician. More to the point, one realizes in reading Brubeck’s own comments one of the reasons why, perhaps, he was undervalued for so long. He was extremely modest about his music and not prone to bragging about it, let alone arguing its merits with critics or fans with ears of stone. I was lucky, once, to be a guest on a jazz radio program where the host talked to Brubeck live via the phone. The man’s humility and graciousness always overrode his desire to be more widely liked or understood. Brubeck always felt that his music spoke for him much more eloquently than he could with words, thus he only spoke up when prodded. Now there is this book, and Jack Reilly’s superb analysis of his music, to rebuild Brubeck’s credentials as one of the finest jazz composers of his era.

The accompanying CD is instructive and fascinating, but not always easy to follow with the printed music for the simple reason that Reilly sometimes improvises beyond the end of the written music. Essentially, the scores reduce the music to its basics, with slow-moving chords so the ear can catch what is going on. There are no pauses of silence between most of the tracks, which sometimes confuses the ear, and in at least one case (Her Name is Nancy) a pause within the track. Sometimes, Reilly plays melody notes entirely different from what is in the score, for instance in Nomad (Afghanistan), where the opening bar is marked as four C-sharps in the right hand but Reilly plays C-sharp, A above, A, C-sharp, with different underlying chords on all four beats, not the single block chord held for four beats as notated. In the second bar he plays a melodic line of four quarter notes, B, G above, G above, B, not the notated eighth notes in the score. Thus you need to keep watching your CD player to figure out where you are. Well, he’s a jazz musician, not a Midi!

This is an excellent book for anyone who wishes to analyze Brubeck’s music harmonically or structurally in any way. For the intermediate jazz student it is even more valuable as a teaching and learning tool.