New York Times

New York Times - 11th September 1972 ©

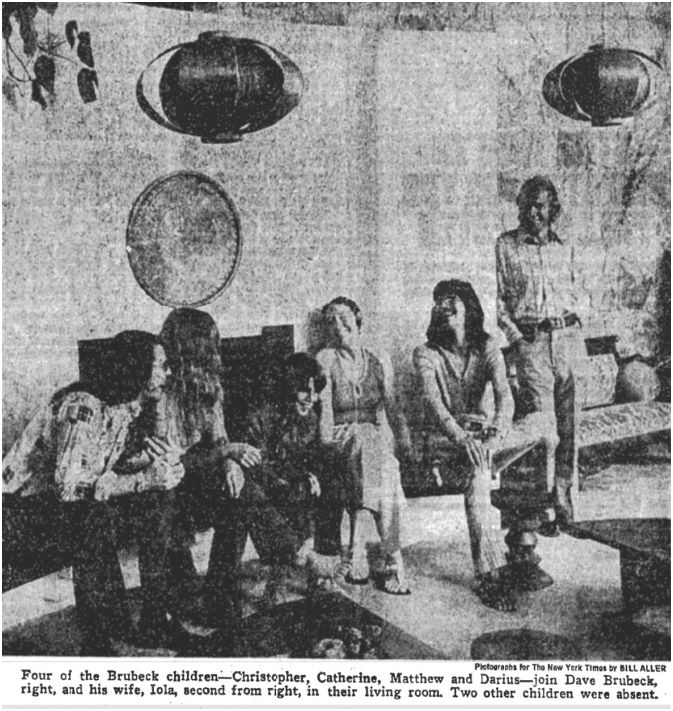

With The Brubeck Family, Stress is Togetherness

Wilton, Conn.

One day recently a man and a woman sat in a parked car in nearby New Canaan and went over some contracts, planned some itineraries and did other paper work. They were waiting while their youngest child, 11‐year‐old Matthew, took cello lesson.

It was like old times for Dave Brubeck, famed jazz pianist timed serious composer, and his wife, Iola. All six of their children have taken private music lessons—three of the sons are now professionals, two having their own performing groups—and the parents of Darius, Michael, Christopher, Catherine, Daniel and Matthew found long ago that work requiring concentration and quiet could be better taken care of in a parked car than at home.

“For a while,” Mr. Brubeck recalled the other day, “Iola was driving the children to 20 lessons a week; it was like a taxi service. And if I was around I'd go along and sit in the car and work. The musical she and I wrote together for Louis Armstrong—it was about jazz musicians being the real ambassadors, and that's what it was called, ‘The Real Ambassadors'—was done mostly while we were waiting for Michael.”

If ever a family lived togetherness, without self‐consciousness but with lots of teasing and laughter and activity, common interests, productivity and the casual bringing in of friends, the Brubecks are it.

The sprawling Japanese house, not far from Wilton in a compound with its own waterfall and fish‐stocked pond, has always been a busy, lively place.

It has been getting busier and livelier, what with father and two sons composing and practicing and getting ready to fulfill engagements, sometimes singly and sometimes together, and with everyone except Mrs. Brubeck playing some instrument or other now and then. (She has helped write lyrics and texts for her husband's works, everything from the jazzy “Take Five” to the cantata “Truth Is Fallen.”)

Now the place on Millstone Road will quiet down a bit; Darius will be  commuting to Wesleyan for a master's degree and Chris is returning to the University of Michigan. On the other hand, Danny, who has been visiting in North Carolina where he attended the School of the Arts, is going to attend high school in Wilton this year so he can play drums with Darius's Ensemble.

commuting to Wesleyan for a master's degree and Chris is returning to the University of Michigan. On the other hand, Danny, who has been visiting in North Carolina where he attended the School of the Arts, is going to attend high school in Wilton this year so he can play drums with Darius's Ensemble.

When asked if there was any problem with competitiveness between father and sons, the members of the family who happened to be In the big, open‐to‐the‐garden living room—father, mother, Darius, Chris, Matthew and Cathy—looked at each other questioningly. Then Cathy asked, “Competitiveness over what? Food?”

There was the usual easy laughter. But Dave Brubeck finally said, “Well, you could say, I guess, that there's some competition over the studio. With three of us now composing, the schedule gets a little tight. What we're probably going to have to do is build another studio outside the house.”

“Danny wants to compose, too; he's already started but the notation is his slowdown,” offered 25‐year‐old Darius, who was named after the French composer Darius Milhaud and is called Dari. He is the only one who has married and he and Sheena, his wife of two years, live down the road.

The talk turned to how Dave Brubeck had got three of his five sons so deeply engaged with music, with perhaps fourth to follow, when many a musician who is a father has given up accomplishing it in a surface way with only, one offspring.

“I started with the first one,” Mr. Brubeck said, “and kept at it with the others.

“When Dari was an infant,” he went on, “I put him on top of the piano and I put Milhaud's ‘Creation of the World’ on the phonograph and he responded to it. He responded even more, though, to Milhaud's ‘Orestes.’ In his crib he heard Bartok, Stravinsky, Copland. Later he conducted with his pistol.”

“That's when I was in my cowboy suit,” said Dari, and everyone laughed fondly at the mental picture this conjured up. (The reason Darius Milhaud figured so prominently was that Dave Brubeck studied composition with him at Mills College in California.)

“The truth is,” Dari went on, “dad's conditioning was so effective that wasn't aware of it. So I felt I just had it, that it had come naturally. Then as I got older music became a form of recreation.”

Chris, who is 20 and has a sevenman group called “New Heavenly Blue” based at the University of Michigan, said, “I used to play cowboy when was 5 and I was taking rip‐roaring piano lessons then.”

Iola Brubeck, a tranctil‐appearing woman, had spoken very little but now she said, “I'm a nonmusician but wanted them exposed to music; all of them have gone through the lessons routine. But with Michael it didn't take; he seems to be a throwback to the ranches.”

Mrs. Brubeck's father, Charles Whitlock, came from a pioneer ranching family in northern California and worked in his youth as a ranch hand and lumberjack before becoming a mechanic for the United States Forest Service. Dave Brubeck's father managed one of the great California ranches and Dave worked on it as one of the hands when he was young.’

Whether or not 23‐year‐old Michael is a. throwback to the men who lived and worked among horses and cattle, he has elected not to pursue a career in music; he has put away his alto saxophone and become a horse trainer.

Cathy, who goes to Simon's Rock College in Great Barrington, Mass., is another Brubeck who intends to keep music at bay. She has stopped studying the flute and hopes to work with children.

The conversation swung to how the Brubecks used to take the first two boys on tour, which meant that Dad and Michael, from infancy on, had to get used to one‐night stands, hopping on and off planes and trains, to camping out and to being squeezed into a Kaiser Vagabond. Dari doesn't think those experiences hurt him. If they left any mark on him and Michael it is in the form of a restlessness that lets, them enjoy going from place to place.

The other four children were taken along only during vacation periods. “We all look at late night movies on TV,” said Chris. “That comes from staying in so many motels.”

There just might not have been any Dave Brube'ck Trio or Quartet if Iola Brubeck had not gotten those first crucial bookings. She had met Mr. Brubeck in the spring of 1942 when his jazz combo played at the College, of the Pacific in Stockton, Calif., where she was an 18‐year‐old, second‐year student on a scholarship and he was 21. They were married that September, few weeks after he joined the Army.

Following his discharge, Mr. Brubeck Ikea to Mills to study with Milhadd, and Mrs. Brubeck took courses in philosophy,’ music history and creative writing.

By late 1949 interest had begun to grow in the trio that Dave Brubeck had formed, but no booking’ agency would take it on. Iola, while looking after 2‐year‐old Darius and the infant Michael, sat’ down and wrote to every college within driving distance of San Francisco, offering at a minimum fee a jazz concert for an assembly or a concertand‐lecture series. The replies started coming in and the college campus circult, which nourished the Brubeck career until it could make a big name on recordings and in concert halls, was on its way.

When the first two children ,got old enough to go to school, Iola Brubeck stopped touring with her husband, except in vacations.

“From about ’51 to ’67 I had to be away 80 per cent of the time,” said Dave Brubeck. So Mrs. Brubeck was left to cope alone during that 80 per cent with six lively youngsters during some of the most critical years of their lives. That they are still lively and thoroughly attached to home but are also profoundly involved with other worthwhile interests is a testimonial to the way she did it.