.jpg)

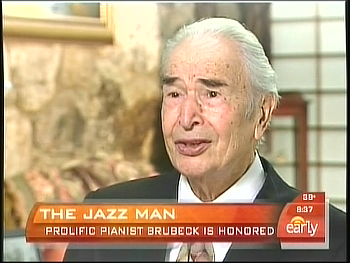

Dave Brubeck: Legend Who Almost Wasn’t (CBS), Dec 24th 2009

Two of the hardest titles to come by are innovator and genius. Dave Brubeck is both, says “Early Show” co-anchor Julie Chen, who recently sat down with the jazz great ; the conversation which will be aired on CBS on December 29th as part of the Kennedy Awards broadcast.

Dave Brubeck is both, says “Early Show” co-anchor Julie Chen, who recently sat down with the jazz great ; the conversation which will be aired on CBS on December 29th as part of the Kennedy Awards broadcast.

But, he told Chen, there were points when his career could have been derailed—before, during and when graduating from college, and when a record company balked at what would become a Brubeck milestone.

Fifty years ago, Brubeck, now 89, was a respected musician who had already made the cover of Time magazine, when his quartet changed jazz forever with the classic tune “Take Five.” They declared independence from the traditional 4/4 jazz rhythm, giving birth to the now classic 5/4 time.

It was included on what’s become the biggest-selling jazz album ever, “Time Out,” which the record label didn’t want to release.

”They said, ‘You’ve broken many unwritten laws,’ “ Brubeck recalled for Chen.” It took a long fight, and then, finally, they put it out as a single ... and it became, when it was a full LP (album), one of their best-sellers.”

Did that surprise him, after being told it was unconventional and wouldn’t work? “Well, l knew people liked it when we played it,” Brubeck responded.

He grew up the son of a cattle rancher and a piano teacher. When it came time for college, his father said no, but his mother insisted. “He said, ‘If he goes, he studies to be a veterinarian,’ “ Brubeck chuckled.” And the first year in zoology, pre-med, the teacher said, ‘Dave, move across to the conservatory, across the lawn, because your mind is not here.’ So I moved!” His love of music won out, but Brubeck almost didn’t get a chance to graduate: the dean discovered he couldn’t read music. “Then, two teachers, professors went to him and said, ‘You’re making a big mistake,’ “Brubeck remembers. “So, the dean said, ‘We’re gonna let you graduate—if you promise never to teach and embarrass this institution!’"

His love of music won out, but Brubeck almost didn’t get a chance to graduate: the dean discovered he couldn’t read music. “Then, two teachers, professors went to him and said, ‘You’re making a big mistake,’ “Brubeck remembers. “So, the dean said, ‘We’re gonna let you graduate—if you promise never to teach and embarrass this institution!’"

Brubeck soon became a musical ambassador, helping to break racial barriers. “My heroes were all African-Americans,” he explained, “and they deserved to be the geniuses of our culture—Duke Ellington and Count Basie. And I just wanted this music to become part of our culture and part of the voice of freedom, wherever we went.”

Over the years, Brubeck has created jazz symphonies, operas, quartets, and cantatas.

Does he play every day? “I wish!” he replied.

And on his actual 89th birthday, Brubeck had a long time wish finally come true: a Kennedy Center honor.

As year-after-year rolled by without his being named, he admits, he began to think it would never happen. “I’m still having trouble believing it’s true!” Brubeck said with a broad smile.