.jpg)

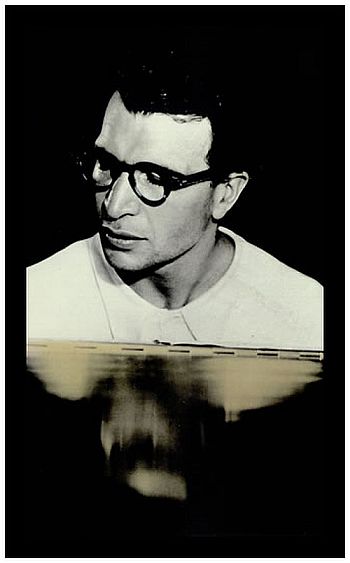

Dave Brubeck, The Biography

Part 1 1920-1948

© Sony Music Entertainment. Reprinted with the permission of the author, Doug Ramsey and Sony Music Entertainment. Copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Some time ago, a woman in Connecticut, where Dave Brubeck lives, was looking for a pianist to play a wedding. Having got hold of a musicians union directory, she called a number she found under the "Piano" heading. Brubeck was considering taking the job, for scale, the minimum amount of pay the union allows a player to accept. But finally the name attached to the phone number registered with the woman. She shrieked in embarrassment, apologized profusely for what she believed had been an insult, and hung up. "Usually, I play at weddings only for close friends," Brubeck joked later. "But I was thinking it over."

“Some time ago, a woman in Connecticut, where Dave Brubeck lives, was looking for a pianist to play a wedding. Having got hold of a musicians union directory, she called a number she found under the "Piano" heading. Brubeck was considering taking the job, for scale, the minimum amount of pay the union allows a player to accept. But finally the name attached to the phone number registered with the woman. She shrieked in embarrassment, apologized profusely for what she believed had been an insult, and hung up. "Usually, I play at weddings only for close friends," Brubeck joked later. "But I was thinking it over."

He may also have been thinking about the years following World War II, when his dream was to make scale. The earliest recording in this collection is from 1946, when that dream seemed closer and there was hope of getting out of the poverty of a struggling musician fresh out of the Army. The most recent recording is from 1991. Brubeck, now famous around the world, still carries the memory of living with his wife and babies in a corrugated tin room without windows.

The music here includes recordings from a period during which Brubeck and his quartet galvanized an entire college generation's interest in jazz, made the cover of Time magazine, became the first instrumental group to sell a million records (Time Out), opened the jazz community to the possibilities of improvisation in time signatures such as 5/4,7/4,9/8,11/4, and 13/4, and was on the road more or less continuously, playing for audiences at home and in India, Poland, Japan, Mexico, Germany, Holland, Argentina, the Soviet Union, and most of the rest of the United Nations.

Brubeck's importance to and influence on jazz are undeniable, except by some of the jazz "elite" and the constituency it has educated to believe that the enormous popularity of the quartet was proof that wide commercial acceptance is tantamount to artistic sellout. The same charge has been made against Louis Armstrong, Cannonball Adderley, the Modern Jazz Quartet, and just about any solvent jazz musician.

FAME AND THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

In 1953, before it was considered commercially successful, the Dave Brubeck Quartet won first place in both the Critic's Poll and the Reader's Poll in Down Beat Magazine. With recognition came detraction. Some of the reasons are rooted in the complexities of ethnocentrism, clannishness, commercialism, and transitory values in our society. Others are as ancient as thejealous ego. But time, not the jazz establishment of the moment, will evaluate the permanence of Brubeck's contributions. It will take into account his work as a pianist whose individualism does not always match the conventional view of what is proper in jazz piano, as a song writer of power and lyricism, as a long-form composer of secular and religious music, and as a leader who harnessed and melded the talents of men with personalities that, like his own, grew out of strength, even obstinacy.

Brubeck needed strength when he emerged from the Army at the end of the war, burning to develop ideas that had germinated through an active musical childhood and his years of studying music at College of the Pacific in Stockton, California. Dave had been playing the piano since he was four years old in Concord, California, where he was born on December 6, 1920. Music was an important part of his life even when, from the age of 13, he started working as a cowboy on the 45,000 acre cattle ranch managed by his father.

RHYTHMS OF THE RANGE

On the family ranch, 1938

On the family ranch, 1938

Brubeck Collection

Wilton Library

The ranch, still owned by the Moffat family, spreads across the parched fastness of San Joaquin, Sacramento, and Amador counties. Its original boundaries were the Mokelumne River north to the Cosumnes, and from the Sacramento River east to the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Brubeck says that as he tended cattle, the rhythms of the ranch fired a fascination with divisions of musical time.

"The first polyrhythms I thought about were when I was riding horseback. The gait was usually a fast walk, maybe a trot," he says, "and I would sing against that constant gait of the horse. Moving the cattle, we might drive them from Oakdale to lone, 40 miles or so. In a round-up, my dad always told me to keep in sight of the cowhands to my left and right, but they could be a mile or so away. The cattle, the horses, everything, got into a rhythm on those hot summer days, except when one of the cattle would turn back and I'd have to get it back with the herd. There was nothing to do but think, and I'd improvise melodies and rhythms."

His imagination was sparked by the sound permutations of anvils in the blacksmith shop, machinery in the hay fields and the one lung gasoline engine that drove the pump forcing water into the stock tanks.

"That little engine was an incredible generator of rhythms. It would take a couple of hours for one of those water tanks to fill. I'd sit there in the shade of the tank listening to the engine and putting other rhythms against it."

H.P. (Pete) Brubeck, Dave's father, was a lifelong cattleman and a championship rodeo roper. I recognized someone familiar when I saw a photograph of Mr. Brubeck on the ranch in his working outfit — Levis, shirt buttoned closely around the wrists to protect against scrapes and insect bites, five-gallon hat cocked over the right eye, the horn of a prize bull in one hand and a halter rope in the other. I was looking at my grandfather and uncles on the family ranch in Montana where I did part of my growing up; the same easy confidence in the stance, the same gaze signaling defiance at the ready. The face might have been painted by Charles Russell. And it has a quality that brings to mind Paul Desmond's celebrated account of meeting and playing with Dave Brubeck for the first time and being struck by this daring pianist "with the expression of a surly Sioux."

THE QUESTION OF INDIAN BLOOD

Paul's poetic image may have reflected reality. Pete Brubeck's heritage had a lot of Germany in it, but Dave told Gene Lees in 1991 that his father, born in 1884 near the Pyramid Lake Indian reservation in Nevada not far from the California border, could be part Modoc, maybe as much as a fourth or more.

"Once in a while, my dad would make a remark that hinted at this heritage, and when I was young he took a picture of me with an Indian boy who was my age. He wrote on it, 'Which is the Indian boy?' Any time he'd mention it, my mother would deny it. And to this day, my dad's younger brother, who's over 90, says it's impossible. But another branch of the family says my grandfather was married three times, once perhaps to an Indian woman."

Dave was Pete's last hope that a son would follow him in the cattle trade. It was too late for the older brothers. They were committed to music. Howard was headed toward a career as a composer and college professor. Henry was already in Stockton playing drums with a band led by Gil Evans, who more than two decades later would become the arranging eminence of the post-war modern jazz movement. Henry later became head of music for Santa Barbara public schools. Dave was born in 1920, Howard in 1916, Henry in 1910.

Dave spent hours on horseback in the isolation of the ranch, riding fence, filling water tanks, and rounding up strays. As a teenager, playing with local bands in places like Angels Camp and Sutter Creek, his intention was always to work on the ranch, even when his mother insisted that he follow in his brothers' footsteps and go to college.

Dave's mother, Elizabeth Ivey (Bessie) Brubeck was the daughter of the man who operated the livery stable in Concord. Henry Ivey spotted Pete Brubeck around the turn of the century when the 16 year-old cowboy delivered a train carload of wild horses and a carload of cattle he had helped round up at his father's ranch near Pyramid Lake.

"The livery stable was sort of the rent-a-car of those days," Dave says, "so my Dad went to rent a saddle horse and hire some hands to help him move the stock to the new family ranch near Concord. My mother was in her early teens. Her father went home that night and told her, 'I met a real young man at the corral today.' My dad soon ran off the other suitors. When my dad finally proposed, my mom's father told her, 'Bessie, if you marry him, you'll never want for a sack of flour.'

THE READING CONUNDRUM

Bessie Brubeck was a classical pianist and a prominent piano teacher. She studied in Great Britain with the influential teacher Tobias Matthay and later with Dame Myra Hess, the legendary pianist known as the Great Lady of Music and the First Lady of the Piano. But Mrs. Brubeck's studies abroad began after she had three sons. The eldest, Henry, went to Europe with her. She came to miss terribly the two sons she had left at home. Deciding against a career as a concert pianist, she returned from London to raise her children and teach piano.

One of her students fooled her. Her youngest son's ear was so adept that he learned to play by listening. She discovered when it was too late, when he was playing well, that David could not read music, that when he stared so intently at the manuscript pages on the piano, he was faking. But it was not just his exceptional ear that led to his cover-up.

"I was born cross-eyed. I had to wear glasses before I got out of the crib. I was very cross-eyed," Brubeck told me. "You see things differently, and I think at first it wasn't clear to me how the music lined up, and I learned I could get by faking it. My mother taught all day long and I could hear the things she was teaching and could pretend that I was reading. I tried to correct it myself, but by then I was 12 or so and it was very difficult to change my habits."

Through weekly visits to the eye doctor from an early age, and through the use of corrective lenses, young Dave's eyes eventually uncrossed. As he got older, his vision improved and his trademark tortoise shell "bebop" glasses were no longer a necessity.

By the time the Brubecks moved to lone, southeast of Sacramento in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Dave's mother was convinced that he was going to be a cowboy, and she never gave him another lesson. Nor did the question of reading music ever come up between them."We never discussed it," he said. "It must have been an embarrassment to her."

Literacy in the language of music, as in the language of words, comes easiest and most naturally when the brain is young and growing and at its peak of receptiveness. Later in life, as Dave was to discover, it comes with great effort. During his teenage years on the ranch he continued to explore the harmonic and rhythmic possibilities of the popular songs of the day. By the time he was in his early teens, he was making money playing the piano, his remarkable ear carrying him through.

The little gasoline engine and the hooves of horses inspired polyrhythm’s. As often as he could, he rode with Pete Brubeck's top cowhand, Al Walloupe from the Miwok tribe, who sang with young Dave and, through his knowledge of Indian songs, became a lifelong friend and musical influence. But the jazz that first moved Brubeck was by pianists Fats Waller and Billy Kyle.

"The first record I ever bought was by Fats Waller, when I was 14. But I had heard the Billy Kyle trio on the radio, even before I heard Fats. The Waller record had "LET’S BE FAIR AND SQUARE IN LOVE" on one side and "THERE’S HONEY ON THE MOON TONIGHT" on the other. When you're working for a dollar a day and the record costs 50 cents, it's a big decision."

More than two decades later, Dave and his hero, Kyle, collaborated at the piano behind Louis Armstrong's vocal on Brubeck's "summer song," heard in this collection. In the mid 1930s, his playing was influenced by Kyle and Waller, but his older dance band colleagues noticed the streak of unorthodoxy that was to baffle or frustrate other musicians for a long time to come.

SCREWING UP THE SHUFFLE RHYTHM

"The band used shuffle rhythms in practically everything, just that steady shuffle rhythm that Jonah Jones had all those hits with later. The leader was a trumpet player and he loved Clyde McCoy. I'd get bored and screw that rhythm up on purpose, break it up, and get dirty looks. And harmony; by the time I got to college at 17, I was really messing with harmony, but I didn't know how to explain it to anybody else."

He had no idea of music as a profession. He was committed to the career his father had in mind for him."I would never have left the ranch if my mother hadn't insisted that I go to college like my two brothers did. I didn't want to go. No way. The compromise was that I would be a veterinarian and come back to the ranch."

Brubeck enrolled at College of the Pacific in Stockton as a pre-medical veterinary student. He lived in a boarding house with several music students. During the progress of his education, which was saturated with science studies, he related his academic situation to theirs.

"I knew, innately, what they were struggling over musically. What I was struggling over was zoology and chemistry, which, innately, I did not know. What my brilliant mind put together was, 'as bad as this is, it would be easier in music.' So I switched over, with no intention of becoming a so-called trained musician. It was just a way of staying in school more easily, because I was a very uneven student. I was likely to get an A in one subject and an F in another."

Now he was music major and his inability to read began to haunt him. Faking it wasn't quite so easy here, where a professor was likely to insist that he be able to describe a progression or the makeup of a chord. The legend at C.O.P. is that Brubeck and three other musicians lived in an enormous basement they called "The Bomb Shelter." The amenities were a cold water faucet, a stove for cooking, and an old upright Starr piano. In the September, 1991, Jazzletter, Dave told Gene Lees about those days.

"WAKE UP BRUBECK"

"....Like, in ear training, I'd usually be asleep, 'cause I'd been working in some joint the night before until two in the morning. There are stories about the teacher saying, 'Well, can anybody play this progression and tell me what I've just played?' Then he'd say, 'Well, if nobody can, then wake up Brubeck.'

"In my own way, I could do it. He'd say, 'What chord is this?' and I'd say, That's the first chord in "don't worry 'bout me.'" Then he'd say, 'Well, explain that, Mr. Brubeck.' I'd go play that chord. He'd say, 'Well can't you say that's a flat ninth?' I didn't know it was a flat ninth. But that's the way I got through." Sometimes he wasn't allowed to explain simply by playing an answer to a musical question. Finally, forced to take a keyboard class, the deceiver was exposed. The professor reported to the dean the inescapable and astounding fact that Dave Brubeck, a senior in a music conservatory, the brother of two distinguished conservatory graduates, the son of a respected music teacher, could not read music.

Sometimes he wasn't allowed to explain simply by playing an answer to a musical question. Finally, forced to take a keyboard class, the deceiver was exposed. The professor reported to the dean the inescapable and astounding fact that Dave Brubeck, a senior in a music conservatory, the brother of two distinguished conservatory graduates, the son of a respected music teacher, could not read music.

"In my final for harmony class, I got an A for ideas and an F for writing the notation down, so he gave me a C. I remember my teacher, Dr. J. Russell Bodley, telling me, 'I couldn't wait to get to your paper because I knew it was going to be the most exciting. Dave, you misspelled most of the chords, but you had the right notes down.' That was typical."

The dean informed Brubeck that he would not be allowed to graduate. But Brubeck had proved to some of the faculty that he had a brilliant aptitude for harmony and counterpoint. He had, in fact, enchanted the counterpoint teacher, who explained to the dean that Brubeck had "written" the best counterpoint of any student he'd ever had. Dr. Bodley, the ear-training and composition professor offered similar praise, and the two of them convinced the dean to let Brubeck graduate. There was, however, a condition; that Brubeck promise "never to teach and embarrass the conservatory." He promised. He was graduated. His teaching has been by example.

Brubeck's father, who had hoped for a son to join him in cattle ranching, was disappointed when Dave turned from veterinary medicine to music. But he offered support and a fallback position.

"He understood, and he said, 'You know we started a herd of cattle that's yours.' He gave me four cows when I graduated from grammar school. He kept books on how they multiplied, kept 'em separate and said, 'These are Dave's,' and he told me, 'You know, if it ever gets too tough on you, you can always come home and you'll have a start in the cattle business.' That was important to me, too, because there were times when I was ready to give up; driving across the country in my Kaiser automobile, trying to keep the family together, without money to stay in a hotel, living in the worst kind of conditions. When it was impossible to keep groups on the road and I wouldn't know how we were going to get to the next town, defeat after defeat after defeat, I'd start thinking about the ranch again."

Dave's herd was maintained until Pete Brubeck's death in 1954. By then, Brubeck's musical fortunes had improved.![Brubeck - with Iola 1942[1] Brubeck - with Iola 1942[1]](http://dbj.silverink.ie/download/1/Images/Images%20For%20Text/.resized_150x179_Brubeck%20-%20with%20Iola%201942[1].jpg) IOLA

IOLA

Not long after his graduation from C.O.P., Brubeck went into the Army. In 1942, when he was on a three day pass, he married lola Whitlock, a student he fell in love with at C.O.P.; "the incomparable, regal lola," Paul Desmond called her.

(Note - further analyses of the importance Iola player in Dave’s career is discussed in a separate part of this Bio Section)

THE SCHOENBERG ENCOUNTER

In another Los Angeles encounter, Brubeck, with high hopes, approached the formidable composer Arnold Schoenberg, a member of the music faculty at UCLA. Brubeck wanted to study with this pioneer of modern music who early in his career moved beyond the norms of tonality and form.

"I had one interview and one lesson," Brubeck recalls. "After I had played him something, he said, 'Why did you write this?' I told him, 'It's what I wanted to show you.' He asked me, 'But do you have a reason for every note? There has to be a reason for every note.' I told him, 'I write it because it sounds good.' He said, 'That's not reason enough; there has to be a reason.' I didn't like his approach and he didn't like mine and that was the end of it. I like much of his music, but I knew we couldn't get along."

After D-Day in 1944, the American military machine in Europe demanded a massive injection of combat troops. Brubeck and many of the other musicians from Camp Hahn were shipped to Europe as riflemen. On his way through San Francisco, he sat in with members of the 253rd American Ground Forces Band stationed at the Presidio. One of those in the jam session was a clarinetist who had taken up alto saxophone the year before. Years later, the alto player, whose name was Paul Desmond, said he had been dazzled by Brubeck's harmonic approach. In an interview for a Down Beat article in September, 1960, Desmond alleged to pianist Marian McPartland doubling as journalist, that he complemented Brubeck as follows: "Man, like Wigsville! You really grooved me with those nutty changes." He said Brubeck replied, "White man speak with forked tongue," a line that was occasionally exchanged between the two over the next three decades to the glee of Brubeck and Desmond and the mystification of nearly everyone who overheard it.

A replacement in Patton's Third Army, 140th Infantry Regiment, A Company, Dave was near the front in the Battle of the Bulge in late 1944 and early 1945. Twice, he found himself behind the German lines when the front moved. He was always near the action, on the verge of being sent into combat. Music saved him.

Waiting for an order to move with his outfit closer to the battle, Brubeck heard a Red Cross girl ask if anyone could play the piano for a show. He volunteered. A colonel who heard him pulled the form required to send an enlisted man into combat and ordered Brubeck and two other musicians to put together a band to entertain the men who had returned from the front to recover from battle fatigue. The band was made up for the most part of soldiers who had been wounded, and it was, to Brubeck's knowledge, the first integrated military unit in World War II.

PFC-IN-CHARGE

For reasons Brubeck can't remember and says he may never have known, the group was called The Wolf Pack Band. A private first class, he had the lowest rank in the band but was ultimately assigned an 020 specialty number, bandleader, and put in charge of an outfit in which he was outranked by all of the members.

"Eventually they wanted to make me a warrant officer," Brubeck says, "but I would have had to live with the officers, and I didn't want to leave the band, so I kept the PFC rating and stayed where I was." Where he was, frequently, was in trouble. The colonel, concerned that everyone qualified to fight was about to be sent to the front lines, ordered Brubeck to load the band on a couple of trucks and "take a Cook's Tour." In other words, he and the band were to get lost until the crisis passed.

"Unfortunately, we drove right into the Bulge, which wasn't the Bulge yet. We saw some guys in a clearing, eating, so we thought we'd play for them. As we were playing, a plane flew over. Since no one had seen an enemy plane for a month, no one thought anything of it. Then it came back, and we saw that it was a German plane. I said, 'Let's get the hell out of here.'

"The driver took a wrong turn, and we were going away from protection, through the enemy lines. It was dark by now, no headlights allowed, and a sentry with a camouflage flashlight waved us through a checkpoint. As we drove through, I realized it was a German soldier and a German checkpoint. We went up the road a way, turned around, gunned the engine, and drove by him as he waved us through again. I thought for sure there would be a tank there ready to blow us to hell.

"When we got back to a sentry point on the American lines, a soldier walked up to us carrying two hand grenades with the pins pulled, ready to use them. One of the guys in the back of the truck was yelling, 'Don't forget the password.' But even after I gave it, this guy was suspicious. I still thought he might drop the grenades into the truck. After a few tense moments, he finally believed who we were. He then explained that earlier the same night Germans wearing American uniforms and driving American trucks had killed all of his buddies at that same sentry point."

Among The Wolf Pack's assignments was the accompaniment of a touring unit of the Radio City Music Hall show which included the Rockettes. This allowed the musicians the luxury of sleeping in hotels rather than haystacks and boxcars or on the ground. But luxury seldom came. As members of an unauthorized band, they had no access to Army instruments. They traded cigarettes for instruments in captured German territory and later in a village in Czechoslovakia known for its instrument making.

None of the Wolf Pack musicians reached anything like Brubeck's prominence. But Johnny Stanley, the master of ceremonies, had a post war comedy hit record called, "IT’S IN THE BOOK." Another member, Leon Pober, was the composer of the song "PEARLY SHELLS" and many other commercial successes and gets credit for "ZEN IS WHEN," in Brubeck's 1964 album, Jazz Impressions of Japan. (CS 9012) Dave remained with the band until he was discharged in 1946 and has stayed in touch with many of its members to this day.

At College of the Pacific, Brubeck had faced discouragement more daunting than sleeplessness and the academic obstacles erected by his inability to read music; he was a jazz musician. As much as individual members of the faculty may have liked Brubeck and admired his gifts, the jazz musician was a species beneath their consideration as a serious artist and Dave's unorthodox ideas about music were resisted and discouraged by some of the faculty and many of the students. Given his single-mindedness and cowboy stubbornness, the opposition may have spurred Brubeck in his determination. Ironically, in developing his jazz, Brubeck was dedicated to experimentation with tonality, harmony, and polyrhythms not unlike qualities in the music of Bartok, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Milhaud, and other pioneers of contemporary "classical" music.

WITH MILHAUD AT MILLS

That made the next stop in his career a considerably more congenial affair. Discharged by the Army in 1946, Brubeck rejoined the wife he had not seen in two years. Under the GI Bill that

made higher education possible for millions of veterans, he entered Mills College in Oakland to study under Darius Milhaud. Pete Rugolo and Dave's brother, Howard, were Milhaud's first male graduate students at this women's college. Howard served for many years as Milhaud's assistant at Mills. The composer of "ALLEGRO BLUES," Howard Brubeck is retired as chairman of the music department at Palomar College in southern California. Rugolo went on to become one of Hollywood's busiest composers, contributing heavily to Stan Kenton's book during the band's peak of success.

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) was a French composer of staggering creativity and output. He wrote at least 450 works with opus numbers. Among them were full scale operas, choral works, orchestral compositions, 18 string quartets, chamber music of every description, and piano pieces. A member of the celebrated group of composers known as The Six that included Francis Poulenc and Arthur Honneger, he was very aware of Igor Stravinsky and Charles Koechlin and jazz.

The result was a style incorporating diatonicism, metric complexity, syncopation, and daring uses of bitonality. Listeners interested in finding common ground between Milhaud and Brubeck may hear it most clearly in Milhaud piano pieces. Those interested in how Brubeck wrote the lessons of the modern masters into his own compositions may refer to his octet pieces "PLAYLAND-AT-THE-BEACH" and "RONDO" (Fantasy OJCCD 101) also under the spell of the Stravinsky of the "EBONY CONCERTO" period.

SOMEPLACE TO GO

"At my lessons with Milhaud," Brubeck says, "he would play through my compositions and make suggestions. One piece was a sonata. I thought the second theme was fine. But he said, 'Put a flat in front of every note in that theme.' I did, and it was transformed, so that when the piece returned to the first theme there was a modulation.

"He always said that modulation was the greatest thing in music that it could lift your spirit... or bring it down. Then he said something I've never forgotten: The reason I don't like 12 tone music is that you're never someplace. "Beethoven loved modulation. So did Brahms. They're always taking us to a new place."

When he arrived at Mills, Dave thought of himself as more a composer than a pianist. He still couldn't read well, but Milhaud immediately saw Brubeck's potential and guided the 26 year old's studies in counterpoint, theory, polyrhythms, and polytonality. He insisted that Dave learn compositional theory and, once satisfied that he had, urged Brubeck to put it into practice. That didn't take much urging. At Milhaud's suggestion he and some of the other Milhaud students put together a band so they could hear what they were writing.

Dave's parents, Pete & Bessie Brubeck

Dave's parents, Pete & Bessie Brubeck  1927 with brother Howard - "Piano Lessons from Mother"

1927 with brother Howard - "Piano Lessons from Mother"  Shortly before joining College with brothers Henry & Howard

Shortly before joining College with brothers Henry & Howard  Dave performing with Wolf Pack band

Dave performing with Wolf Pack band  Private Dave Brubeck

Private Dave Brubeck  The Wolf Pack Band

The Wolf Pack Band  Dave with Darius Milhaud - Mills college

Dave with Darius Milhaud - Mills college