.jpg)

Dave Brubeck, The Biography

Part 2 1920-1948

© Sony Music Entertainment. Reprinted with the permission of the author, Doug Ramsey and Sony Music Entertainment. Copyright protected; all rights reserved.

The Octet, Trio & First Quartet

(Note - Discussed in separate part of this Bio section)

DESMOND REDUX Dave had left standing instructions with lola that if Paul Desmond ever showed up, she should not let him in the house. But one day, the Jack Fina experience behind him, Desmond came to the door. In New York, he had heard a recording of the Dave Brubeck Trio on a jazz radio station. lola let him in. Dave was on the back porch pinning diapers to the clothes line.

Dave had left standing instructions with lola that if Paul Desmond ever showed up, she should not let him in the house. But one day, the Jack Fina experience behind him, Desmond came to the door. In New York, he had heard a recording of the Dave Brubeck Trio on a jazz radio station. lola let him in. Dave was on the back porch pinning diapers to the clothes line.

lola was susceptible to Paul's charm from the first time she met him. She told Gene Lees 40 years later that Desmond looked so forlorn, she went out back and told her husband, "You just have to see him." Brubeck did and, lola said, "...he was full of promises to Dave. He said, 'If you'll just let me play with you, I'll babysit, I'll wash your car."

Brubeck was unable to keep up his resistance. The partnership was back on, at least in spirit. But making the trio a quartet was impossible financially because club managers discouraged anything that might jeopardize the growing success of the trio. Desmond sat in, but the businessmen interested in the modest fortunes of the group were not particularly happy when he did.

Nonetheless, when the trio was booked into Los Angeles, Desmond went along to sit in at The Haig and later at Zardi's. Dave's family also went to L.A. The Brubecks had been living in an apartment in San Francisco and now rented a tiny cottage on the beach at Santa Monica. They had put money down on a house near San Francisco. When the work in Los Angeles ended and it came time to close on the house, Dave and lola put Darius and Michael in the car and drove all night to keep the appointment. Brubeck remembers having lola periodically slap him to keep him awake during the 400 mile drive.

They arrived on time, to discover that the deal on the house had fallen apart. Their down payment money was tied up in escrow. Most of their belongings were in storage. They had no place to live. So when a booking materialized at the Zebra Lounge in Honolulu, Brubeck took the trio, the wife, and the kids to Hawaii. Stone broke, living in cramped quarters, eating food from cans that had been dented and sold at reduced prices, the Brubecks' fortunes were at a low ebb.They got lower.

Dave Brubeck & Cal Tjader

Dave Brubeck & Cal TjaderThe beaches of Honolulu provided sunshine, water, free recreation, and distractions from poverty. To Dave, lola and the boys, the Tjaders, bassist Jack Weeks, and Dave Van Kriedt, afternoons on the beach were relief from ungenteel poverty. Weeks had replaced Ron Crotty in the trio and Van Kriedt was in Honolulu playing a separate job. They were all together one afternoon when Dave, diving through waves, hit a sand bar and wrenched his neck with so much force that an ambulance driver, noting the angle of the head, thought the injury was fatal.

"I heard him calling ahead on his two-way radio, telling them that he was bringing in a DOA; dead on arrival. I thought he was right," Brubeck says. "I was going in and out of consciousness."

The first hospital he was taken to rejected the patient for inability to pay. When it was established that he had been in the service, arrangements were made for him to be admitted to Tripler, a Veterans Administration hospital. Late that night, lola, who had seen Dave being taken away, got a call informing her that her husband was probably not going to be paralyzed, as doctors had at first feared, that, in fact, he was showing improvement.

Nonetheless, the damage to vertebrae and nerves required him to be in traction for three weeks, ending the job at the Zebra Lounge and putting the Dave Brubeck Trio out of business. Tjader and Weeks went home and formed a new group. Nearly 40 years later, Brubeck still feels pain in his back, neck, and fingers; the legacy of his accident in the Hawaiian surf and a reminder that the outcome could have been infinitely worse.In traction, on his back painfully scribbling a note to Desmond, Dave wrote, "Maybe now we can start the quartet." Desmond saved the note all his life.

AT LAST, THE QUARTET

Out of the hospital and back in San Francisco, Dave convalesced, then finally got together with Desmond in early 1951 and formed the first Dave Brubeck Quartet. Desmond had kept eating by taking a job in the reed section of the band led by Alvino Rey, who was several years

The Dave Brubeck Qaurtet 1951 Paul Desmond, Herb Barman

The Dave Brubeck Qaurtet 1951 Paul Desmond, Herb BarmanDave Brubeck & Wyatt "Bull" Ruther

beyond and several pegs below his success in the 1940s with an admired show band. By now, his leadership attempt happily behind him, Desmond had no desire to be anything but a sideman and leave the worrying to someone else. The inclination was so strong that it extended to his business relationship with Brubeck. Throughout all but the earliest years of their career together, they never had a signed contract.

"Paul and I never had an argument about money," Brubeck told Gene Lees. "He never looked at the books. He never asked the attorney to see anything. He said,"Whatever you say is right".When Paul died, by terms of his will, his share of royalties was left to the American Red Cross, which still receives proceeds of the group's recordings, and royalties from Desmond's universally popular composition "TAKE FIVE."

The trio had been a success, but the change to a quartet meant a rebuilding challenge. Fred Dutton and Herb Barman were the initial bassist and drummer, with Wyatt "Bull" Ruther or Norm Bates playing bass and Lloyd Davis or Joe Dodge on drums as the band evolved. After the trio dissolved, Cal Tjader had gone on to work with Alvino Rey, then formed his own band before joining George Shearing in 1953. Ron Crotty was back with Brubeck for much of 1953 and 1954.

The group worked in the Bay Area, mostly at the Blackhawk, with occasional forays into southern California or the Northwest. But before the end of 1951, they began to gain attention. The band found itself in demand in clubs around the country. Performances of the spirit, freshness, and intricacy of "LOOK FOR THE SILVER LINING" (in this collection), struck a chord (altered, augmented, or diminished; rarely orthodox) with listeners.

BRUBECK TIME

The improvement in fortunes extended to domesticity. There was a new real estate transaction, and this time it did not collapse. By the middle of 1954, a house in the Oakland Hills contained six Brubecks, Christopher having made his appearance in 1952 and Catherine in 1953. Dave liked it there. He liked it so much that even though national success was in the air, he was on  the verge of ignoring it in favor of spending the rest of his career gigging around the Bay Area. There were trips east, but as late as 1954 Brubeck was reluctant to commit himself to the road life that would be required to achieve and maintain major stardom.

the verge of ignoring it in favor of spending the rest of his career gigging around the Bay Area. There were trips east, but as late as 1954 Brubeck was reluctant to commit himself to the road life that would be required to achieve and maintain major stardom.

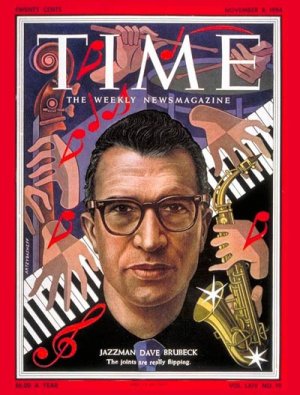

In 1954, Brubeck received a boost so unlikely for a jazz musician that the mere thought of it might send him into gales of cynical laughter. time magazine made him the subject of its main article in the November 8, 1954, issue, with an Artzybasheff cover painting of Dave and a caption paraphrasing his boyhood piano idol, Fats Waller: "The joints are really flipping." In the mid-50s, before the pervasive hype of television diluted the impact of every print medium, a cover story in time was a national event. It brought massive attention to the subject.

By then, he and Fantasy had agreed to an amicable separation and Dave had signed an agreement with Columbia Records. But in the overlapping commitments to the two companies, there were to be three more Brubeck albums for Fantasy: in 1957 one of solo piano, and another reuniting the quartet with tenor saxophonist and composer Dave Van Kriedt, Brubeck's boon companion from the Mills College and octet days. In 1961, long after Brubeck had become, with Miles Davis, one of Columbia's two major jazz artists, he recorded a quartet album for Fantasy with clarinetist Bill Smith, another octet alumnus, replacing Desmond.

THAT'S HOW IT WAS, MOVING EAST

In 1959, while Brubeck vacillated over whether to aim for a big career, his attorney, James R. Bancroft, asked him, in effect, whether he was interested in getting out of debt and being able to put his children through college. The family was more than broke; Dave recently had paid off a loan to cover back taxes. Bancroft persuaded Brubeck to rent the Oakland house, go on the road for a year and move his family to the East Coast, near the sources of most of the potential work in clubs and at the colleges where the band had become increasingly popular. In comparison with the East, there wasn't nearly as much work for jazz musicians out West in those days. He could always move back to the house in the hills above the bay. A Columbia Records executive, Irving Townsend, was about to take over the label's jazz operations on the West Coast and offered to let Brubeck rent his house in Wilton, Connecticut. Dave and lola took a deep breath and made the move.

The Dave Brubeck Qaurtet 1956 on top of Dave's Oakland home

The Dave Brubeck Qaurtet 1956 on top of Dave's Oakland homePaul Desmond, Joe Dodge, Dave & Norman Bates

The house, one of a dozen in a colony owned by a woman who liked to rent to artists and writers, was in the woods. It had openness, light, and lots of room. The Brubecks liked living there, and Dave enjoyed being able to spend time with his family rather than chewing it up traveling back and forth from coast to coast. Eventually, they decided to sell the house in the Oakland Hills and build their own place in Wilton, an establishment immediately christened by Desmond "The Wilton Hilton." Visitors remember a piano in every room, including the kitchen. From its hill, the house looks down and across a sweep of the property's 20 acres of meadow, streams, and woodland.

Brubeck's career had begun to show that it had the potential for steady, respectable growth. Now it took off. His record sales leaped, not only the Columbia recordings with Desmond, Bob Bates, and Joe Dodge, but the ones on Fantasy as well..jpg) Desmond's importance to the success of the quartet is unquestioned, especially by Brubeck. Both of them told me on several occasions that even the stunning moments of contrapuntal improvisation in the best of their Fantasy and Columbia recordings did not approach the peak of what Desmond called their "inspired madness" at the Band Box and later when he sat in with the trio. There's a hint of it in the 1952 Storyville album that for the next 25 years remained Paul's favorite, more than a hint in the 32 bars of counterpoint in the live broadcast of "LOOK FOR THE SILVER LINING" from 1951, and an intense dose of it as Dave supplies his partner harmonic direction and rhythmic accents in "LE SOUK," 1954, one of Desmond's greatest flights of invention.

Desmond's importance to the success of the quartet is unquestioned, especially by Brubeck. Both of them told me on several occasions that even the stunning moments of contrapuntal improvisation in the best of their Fantasy and Columbia recordings did not approach the peak of what Desmond called their "inspired madness" at the Band Box and later when he sat in with the trio. There's a hint of it in the 1952 Storyville album that for the next 25 years remained Paul's favorite, more than a hint in the 32 bars of counterpoint in the live broadcast of "LOOK FOR THE SILVER LINING" from 1951, and an intense dose of it as Dave supplies his partner harmonic direction and rhythmic accents in "LE SOUK," 1954, one of Desmond's greatest flights of invention.

That accompaniment is the work of a man in profound concentration and support, deep in the interaction of emotions and intellects that constitutes jazz improvisation. It epitomizes and symbolizes the selflessness and interdependence that in its finest moments make jazz an act of cooperative creation without parallel in the performing arts. The frequency of those moments in the Brubeck group is what led bassist Eugene Wright to tell a fellow musician who came backstage one night to question Wright's presence in an otherwise white band, "Look, man, there's a lot of love in this group."

The power and weight of many of Brubeck's solos have led his critics to charge him with the sin of heavy-handedness, excessive romanticism, bombast. Once in the 1960s when we were discussing jazz criticism, an activity he regards with alternate amusement and frustration, he said, "The word bombast keeps coming up, as if it were some trap I keep falling into. Damn it, when I'm bombastic I have my reasons; I want to be bombastic. Take it or leave it."

THE ACCOMPANIST

Many critics, full of admiration for Desmond, wondered how he could put up with what they considered the insensitivity of Brubeck's piano playing. They did not hear or could not hear what led Desmond, in his most serious moments of discussing his friend, into effusions of praise for the attentiveness, delicacy, and suggestiveness of Brubeck's accompaniments.

Ignoring the success of the early trio, it was often alleged that without Desmond, Brubeck would never have made it. In that invaluable interview with Marian McPartland, Paul responded, plainly: "I never would have made it without Dave. He's amazing harmonically, and he can be a fantastic accompanist. You can play the wrongest note possible in any chord, and he can make it sound like the only right one.

"I still feel more kinship musically with Dave that with anyone else, although it may not always be evident. But when he's at his best, it's really something to hear. A lot of people don't know this, because in addition to the kind of fluctuating level of performance that most jazz musicians give, Dave has a real aversion to working things out, and a tendency to take the things he can do for granted and most of his time trying to do other things. This is okay for people who have heard him play at his best, but sometimes mystifying to those who haven't."However, once in a while somebody who had no use for Dave previously comes in and catches a really good set and leaves looking kind of dazed."

.jpg) Dave & Paul Storyville 1954

Dave & Paul Storyville 1954In the quartet, Brubeck's taste for a little bombast extended to the exuberances of drummers. In a few places on the celebrated Jazz Goes To College album he can be heard encouraging the bass drum detonations inserted into his solos by Joe Dodge. "Yeah, Joe," he exclaims, whereupon Dodge launches another little mortar attack.

Desmond's idea of appropriate drumming was more in line with that of one of his heroes, Lester Young. Young had been conditioned in his Count Basic days to the impeccable ball-bearing smoothness of Jo Jones and he spent much of the rest of his career discouraging the enthusiasms and paradiddle fills of those he sometimes called "the bebop kiddies."

"Just a little tinky-boom," Pres used to instruct his percussionists. "Don't drop those bombs back there." It's no wonder that Desmond loved to play with Connie Kay, the former Lester Young drummer who took his subtlety and mastery of time to new levels with the Modern Jazz Quartet.

On the other hand, and both feet, there was Joe Dodge, succeeded by Joe Morello. Dodge, an old San Francisco hand, was a bear of a man, a swinger capable of using wire brushes to drive the time unobtrusively but whose temperament had something in common with that of a bombardier. Desmond was fond of Dodge's playing and arranged a truce under which Dodge would keep things down to, at maximum, a medium roar when Paul was soloing.

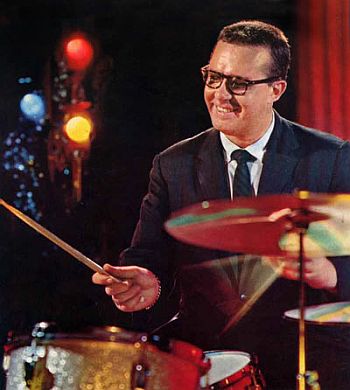

THE ADVENT OF JOE MORELLO

"When [Joe] Dodge returned to San Francisco, Morello left Marian McPartland to join Brubeck. Even though he was hired at Desmond's recommendation, the truce seemed likely to be supplanted by some other condition. Open warfare comes to mind. "Joe Dodge told me he had to leave the group and go back home," Brubeck recalls. "Paul said we should hire Joe Morello. He said Morello was a fantastic drummer who always played softly, with brushes. I went over to hear him with Marian and was knocked out."

"Joe Dodge told me he had to leave the group and go back home," Brubeck recalls. "Paul said we should hire Joe Morello. He said Morello was a fantastic drummer who always played softly, with brushes. I went over to hear him with Marian and was knocked out."

Morello says he remembers Brubeck and Desmond coming into the Hickory House in New York City several times to listen to the McPartland trio."I had been planning on leaving Marian's group anyway," Morello recalls. "There was an audition and an offer from Tommy Dorsey, but his manager got cute with money and while that was on hold, Dave called and asked if I would be interested in joining his group." Morello did not jump at the opportunity.

"I met him at the Park Sheraton in New York, where he was staying. I told him the times I'd heard his band at Birdland, the spotlight was on him and Paul, and the bass player and drummer were out to lunch in the background somewhere. I told him I wanted to play, wanted to improve myself. He said, 'Well, I'll feature you."

The Brubeck group left on a tour, with Joe Dodge still on drums. When the quartet returned near the end of 1955, Morello says he told Dave, "Let's try it. Maybe you won't like my playing and I won't like the group. There's no use signing anything until we're really sure." In lieu of a contract, they exchanged telegrams confirming their intentions.

"Two days later," Morello says, "I got a call from Tommy Dorsey's manager. He said, 'You got the job. Tommy's gonna give you the money.' I told him it was too late, I'd just signed with Brubeck. 'Oh, you don't want to play in Birdland all your life,' he said. 'Look what we did for Buddy Rich and Louis Bellson.' I told him, 'You didn't do anything for Buddy Rich and Louis Bellson. Look what they did for your band.' Brubeck sent Morello some of the quartet's records so he could hear the pieces they would play on his first appearance with the band, a television show in Chicago. They included "I’M IN A DANCING MOOD," "THE TROLLEY SONG" and "TWO-PART CONTENTION," "very basic things with basic tempo changes," Morello says. He flew to Chicago and went to the studio for a rehearsal. But Brubeck's plane was delayed and Dave got there barely in time to do the TV program. Those were the days before videotape. The performance was live and, in the quartet's case, unrehearsed. Morello's debut with the band was flawless.

Brubeck sent Morello some of the quartet's records so he could hear the pieces they would play on his first appearance with the band, a television show in Chicago. They included "I’M IN A DANCING MOOD," "THE TROLLEY SONG" and "TWO-PART CONTENTION," "very basic things with basic tempo changes," Morello says. He flew to Chicago and went to the studio for a rehearsal. But Brubeck's plane was delayed and Dave got there barely in time to do the TV program. Those were the days before videotape. The performance was live and, in the quartet's case, unrehearsed. Morello's debut with the band was flawless.

"When it was over, Dave said to the guys, 'Joe played these things like he wrote 'em.' But, really, they were very simple. So it went fine, and then we went into the Blue Note for a week."The first night at the club, Brubeck had Morello use sticks as well as brushes and gave him a short solo. Joe says the solo got "a little standing ovation" and that Desmond left the stand for the dressing room, where he turned to face Brubeck and deliver an ultimatum: "Morello goes or I go."

"Joe could do things I'd never heard anybody else do," Brubeck says. "I wanted to feature him. Paul objected. He wanted a guy who played 'time' and was unobtrusive. I discovered that Joe's time concept was like mine, and I wanted to move in that direction."

Brubeck had begun his time experimentation in 1946 with the octet. Cal Tjader was a drummer with a natural aptitude for time flexibility, as he demonstrated on the octet's "CURTAIN MUSIC" and with the trio in "SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN," another venture into the mysteries of six-beat bars. "Cal was the most natural musician I've ever heard, one of the very best drummers," Dave says, "and the first night he brought vibes to the job, it was as if he'd been playing them all his life." Brubeck's swimming accident ended his and Tjader's extension of jazz time signatures, and now Morello represented a chance to revive it.

Morello was not a famous drummer when he joined the Brubeck Quartet. He was a respected one, particularly among other drummers, for his speed, control, flexibility, and technique. It was frequently said that only the formidable Buddy Rich had more technique ('"chops," in the argot of the trade) than Morello. There were serious disagreements among musicians over whether Morello's feet may not have been just a trifle faster than Rich's. Morello wasn't about to let all those chops go to waste, which was okay with Brubeck. But it was clear to Desmond from the outset that in his musical life, Lester Young's ideal of a little tinky-boom was a rapidly receding golden memory.

THE BLUFF

"In that first week, Paul said I had to get another drummer," Brubeck says. "I told him I wouldn't. I didn't know whether Paul and Norman would show up that night. They came to a record session for Columbia in Chicago during the day, but they wouldn't play. So Joe and I recorded as a duo for three hours. And they told me they were going to leave the group. And I said, 'Well, there'll be a void on the stand tonight because Joe's not leaving.

"So, I went to the job and, boy, was I relieved to see Paul and Norman. But I wasn't going to be bluffed out of Joe. It was not discussed again. That was the end of it".

Paul Desmond & Joe Morello

Paul Desmond & Joe Morello ''Paul knew that Morello was one of the greatest drummers who ever lived, but what he wanted was a steady beat. Some nights Joe would do more than that and Paul would say, ‘Please don't do adventures behind me.' Later, of course, Joe and Paul became very close."

In the months following the failed bluff, what Brubeck has called an "armistice" was set up, but the situation more closely resembled an edgy cease-fire. It was described by Robert Rice in a New Yorker profile of the quartet: "...bloody war was likely to rage whenever the quartet played, with Brubeck doing his best to mediate between Morello on the one hand and Bates and Desmond on the other."

Brubeck was able to make the center hold through all the internecine battles over tempos, volume, and drum fills during solos. Despite their powerful disagreements about how Morello's skills should be deployed, Dave was able to take advantage of the respect Morello and Desmond had for one another's abilities. The respect was ultimately to grow into genuine affection, but that was at the end of a rough road.

“For a while it was uncomfortable with Paul," Morello told me in 1992. "But as time went on, it worked out. We became very close and used to hang out together. The last four or five years we hung out quite a lot, actually." Morello's phrasing and inflection were uncannily like Desmond's when he said that. "I think the world of Paul," Joe said."No, it was more than that. I loved the guy."

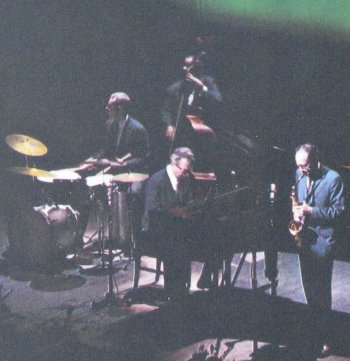

The Classic Quartet Paul, Dave, Joe & Eugene

The Classic Quartet Paul, Dave, Joe & Eugene“I've always tried to hire great musicians," Brubeck says. "But they've got to be great people too. There has always been real closeness, going back to the days with Cal, even after he left, and Ron Crotty, Joe Dodge, and the Bates Brothers, all those guys. Bill Smith started with me in the fall of 1946, and he begins and ends this collection." And, echoing Gene Wright, Brubeck adds, "You can't imagine how much love there was in this band."

Since I began hearing the quartet in person as often as I could in the mid-1950s, I've been convinced that one of the reasons for its huge success, though obviously bound up in the music, is non-musical. It was the musicians' huge, open, unselfconscious enjoyment of one another. Call it the "yeah" factor.

A lot of the hype surrounding the Brubeck Quartet portrayed them as representative of cool jazz. Their stage manner, like much of their music, was anything but cool. Listening with intensity and appreciation to one another, Desmond, Brubeck and the others expressed approval. "Yeah" is an expression of high praise among jazz musicians. This band had a high "yeah" index, and it was infectious. If they liked each other that much, it was difficult for an audience to be aloof from four tall men having a very good time creating serious music.

THE IMPORTANCE OF EUGENE WRIGHT The quartet was entering its period of greatest success. With the departure in 1958 of Norman, the second of the three bass-playing Bates brothers to have worked with Brubeck, Eugene Wright joined the band and the roster was set until the Dave Brubeck Quartet disbanded on December 26, 1967.

The quartet was entering its period of greatest success. With the departure in 1958 of Norman, the second of the three bass-playing Bates brothers to have worked with Brubeck, Eugene Wright joined the band and the roster was set until the Dave Brubeck Quartet disbanded on December 26, 1967.

Wright had led his own band when he was in his early twenties in his native Chicago, then worked with Gene Ammons, Count Basic, Arnett Cobb, Buddy DeFranco, and Red Norvo. When he joined Brubeck, he had been the bassist for three years in the remarkable edition of the Cal Tjader Quartet that also included pianist Vince Guaraldi. A powerful bassist known for his steadiness and swing, he satisfied Desmond's basic requirements.

But Wright was also interested in Brubeck's time explorations and during his first months with the quartet grew significantly in that dimension. An educator by temperament, and later in fact a conservatory teacher, Wright's roots were always firmly attached to the basics and his mind was always open to new musical ideas.

In a recent conversation, Gene recalled his doubts when Brubeck asked him to join the band. They resembled Morello's. He told Dave he wasn't sure they were compatible. "I went over to his place so we could try each other out," Wright said, "and we had a ball playing, hit it off right away. We both love to swing. But I told him, 'I don't know if I can make it with your friends.'

When he got together with all three, Wright discovered a high level of musicianship, naturally, and he found a bond with Morello that resembled the instant rapport Brubeck and Desmond had discovered a decade earlier.

"Right away, Joe and I were as one. It was like Jo Jones and Walter Page with Count Basie. It was right from the beginning. When musicians used to ask me how I could play with that band, I told them they weren't listening. I told them I was the bottom, the foundation; Joe was the master of time; Dave handled the polytonality and polyrhythms; we all freed Paul to be lyrical. Everybody was listening to everybody. It was beautiful. Those people who couldn't accept it were looking, not listening."

Wright was not the first black musician in the Brubeck quartet. Wyatt "Bull" Ruther was the bassist in 1951. Drummer Frank Butler also worked briefly with Brubeck in the early days. Joe Benjamin replaced Wright for a period in 1958, during which he recorded the Eurasia album and Newport '58 with the quartet. But Gene returned to the group in '59. His arrival coincided with the upswing in popularity that increased the demand for the band and put it in high visibility.  Through the 1950s and '60s, the track led straight ahead through the slings and arrows of outrageous critics, the good fortune of a gold single ("TAKE FIVE”/ "BLUE RONDO A LA TURK”) and much of Earth's geography. In 1958, following a series of concerts in the United Kingdom, the band played in many of Europe's major cities and toured for the Department of State in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, India, East and West Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Afghanistan. Later, there were tours of Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Mexico, and South America. Behind the Iron Curtain, there were a dozen memorable concerts in Poland followed by concerts in Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Romania. It was not until 1987 that the Dave Brubeck Quartet finally had the opportunity of performing in the then Soviet Union. Included here is the version of "TRITONIS," recorded on that memorable trip to Moscow, and never released until now.

Through the 1950s and '60s, the track led straight ahead through the slings and arrows of outrageous critics, the good fortune of a gold single ("TAKE FIVE”/ "BLUE RONDO A LA TURK”) and much of Earth's geography. In 1958, following a series of concerts in the United Kingdom, the band played in many of Europe's major cities and toured for the Department of State in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, India, East and West Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Afghanistan. Later, there were tours of Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Mexico, and South America. Behind the Iron Curtain, there were a dozen memorable concerts in Poland followed by concerts in Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Romania. It was not until 1987 that the Dave Brubeck Quartet finally had the opportunity of performing in the then Soviet Union. Included here is the version of "TRITONIS," recorded on that memorable trip to Moscow, and never released until now.

INSPIRATION ABROAD Some of the quartet's best performances took place during these trips, among them the 1958 Copenhagen concert recording of "Tangerine" included here. The sights, cultures, people, and music the quartet encountered in their travels inspired Brubeck's compositional muse. Out of them came "KOTO SONG," "THE GOLDEN HORN," "MARBLE ARCH," "LA PALOMA AZUL," "RECUERDO," and "BLUE RONDO A LA TURK".

Some of the quartet's best performances took place during these trips, among them the 1958 Copenhagen concert recording of "Tangerine" included here. The sights, cultures, people, and music the quartet encountered in their travels inspired Brubeck's compositional muse. Out of them came "KOTO SONG," "THE GOLDEN HORN," "MARBLE ARCH," "LA PALOMA AZUL," "RECUERDO," and "BLUE RONDO A LA TURK".

Travel also led to the title of the book Desmond talked about for years but never quite got around to writing. The title was to be a question he claimed was asked by airline stewardesses around the world: "How many of you are there in the quartet?"

The book, in fact, was one of the reasons the quartet broke up after 17 years. Desmond wanted time to write, an activity George Bernard Shaw and Charles Dickens, but very few others, have found compatible with constant travel.

.jpg) Dave & Paul Storyville 1954

Dave & Paul Storyville 1954